-

Отладка и тестирование программы

Отладка

программы является итеративным процессом

обнаружения и исправления ошибок и

обычно требует последовательного

выполнения четырех этапов:

-

выявления

ошибки; -

локализации

ошибки в тексте программы; -

установления

причины ошибки; -

исправления

ошибки.

Некоторые

ошибки проявляются после первого же

запуска программы на выполнение, и для

их обнаружения не надо прибегать ни к

каким специальным средствам. Некоторые

ошибки проявляются в случайные моменты

работы программы. С такими ошибками

справиться труднее всего – зафиксировать

условия возникновения ошибки, понять

причину ошибки и устранить ее. С целью

обнаружения подобных ошибок осуществляется

тестирование

программы–

ее выполнение для специально подобранных

представительных контрольных примеров

– тестов. Тест

– это такой

набор исходных данных, для которого

вручную или другим способом просчитаны

промежуточные и конечные результаты и

который может быть использован для

получения информации о надежности

проверяемой программы.

Тестирование

программы должно включать в себя прогон

трех видов контрольных примеров:

нормальных ситуаций, граничных ситуаций

и случаев неправильных данных.

Нормальные

случаи –

это примеры с правильными входными

данными. Если программа не работает в

подобных случаях, она требует серьезных

переделок. Граничные контрольные примеры

помогают установить, способна ли

программа нормально реагировать на

особые случаи во входных данных. Граничные

примеры

представляют собой данные, которые,

будучи математически корректными,

приводят программу к необходимости

работать особым образом. Неправильными

являются

такие данные,

которые расположены вне допустимого

диапазона. Примеры с неправильными

данными должны быть обработаны

соответствующим образом, поскольку в

повседневной эксплуатации программе

придется иметь дело и с неверными

входными данными.

После того как

ошибка обнаружена, необходимо найти в

исходном тексте программы то место, в

котором она возникала, – локализовать

ошибку. Можно

использовать ряд различных методов

отладки, позволяющих обнаружить

расположение ошибки; выбор существенно

зависит от особенностей ситуации.

Большинство программистов начинают с

неформального метода, известного под

названием проверка

за столом. Используя

контрольный пример, который привел к

ошибке в программе, программист

аналитически трассирует листинг

программы в надежде локализовать ошибку.

Проверка за столом – это хороший метод,

поскольку он заставляет программиста

детально понять работу программы. Если

применение метода проверки за столом

оказалось бесплодным, нужно использовать

специальные методы и способы отладки,

позволяющие наблюдать за передачей

управления в программе и за изменением

значений наиболее важных переменных.

Полученная отладочная информация

позволит локализовать подозрительные

ситуации, провести анализ и выявить

причину ошибки, устранить ее, а затем

продолжить поиск других ошибок.

-

Причины и типы ошибок

В общем случае

ошибки могут возникать на любом этапе

разработки программы, причина ошибок

может быть связана с недопониманием

сути задачи, недостатками проектирования

алгоритма, неправильным использованием

языковых средств. При выполнении

программы ошибки разного типа проявляют

себя различным образом, и их принято

подразделять на следующие группы:

-

синтаксические

ошибки; -

семантические

ошибки; -

логические

ошибки.

Синтаксические

ошибки –

это ошибки, проявляющиеся на этапе

компиляции программы и возникающие в

связи с нарушением синтаксических

правил написания предложений используемого

языка программирования (к таким ошибкам

относятся

пропущенные точки с запятой, ссылки на

неописанные переменные, присваивание

переменной значений неверного типа и

т. д.). Если компилятор встречает в

тексте программы оператор или описание,

которые

он не может интерпретировать, то он

позиционирует курсор на место обнаруженной

ошибки и

в строку статуса выводит сообщение,

содержащее номер ошибки и ее краткое

описание.

Семантические

ошибки – это

ошибки, проявляющиеся на этапе

выполнения программы при ее попытке

вычислить недопустимые значения

параметров или выполнить недопустимые

действия. Причина возникновения ошибок

данного типа связана с нарушением

семантических правил написания программ

(примером являются ситуации

попытки

открыть несуществующий файл или выполнить

деление на нуль). Если программа

обнаруживает ошибку такого типа, то она

завершает свое выполнение

и

выводит

соответствующее сообщение в окне Build,

содержащее номер строки с ошибкой и ее

возможный характер. Список сообщений

можно просмотреть с помощью команды

меню View/Debug

Windows/Event

Log.

При выполнении программы из среды Delphi

автоматически выбирается соответствующий

исходный файл и в нем находится

местоположение ошибки. Если же программа

выполнялась вне среды и в ней появилась

ошибка данного типа, то необходимо

запустить

среду и найти вызвавший ошибку оператор.

Логические

(смысловые) ошибки – самые

сложные и трудноуловимые, связанные с

неправильным применением тех или иных

алгоритмических конструкций. Эти ошибки

при выполнении программы могут проявиться

явно (выдано сообщение об ошибке, нет

результата или выдан неверный результат,

программа «зацикливается»), но чаще

они проявляют себя только при определенных

сочетаниях параметров или вообще не

вызывают нарушения работы программы,

которая в этом случае выдает правдоподобные,

но неверные результаты.

Ошибки первого

типа легко выявляются самим компилятором.

Обычно устранение синтаксических ошибок

не вызывает особых трудностей. Более

сложно выявить ошибки второго и особенно

третьего типа. Для обнаружения и

устранения ошибок второго и третьего

типа обычно применяют специальные

способы и средства отладки программ.

Выявлению ошибок второго типа часто

помогает использование контролирующих

режимов компиляции с проверкой допустимых

значений тех или иных параметров (границ

индексов элементов массивов, значений

переменных типа диапазона, ситуаций

переполнения, ошибок ввода-вывода).

Устанавливаются эти режимы с помощью

ключей

компилятора,

задаваемых либо в программе, либо в меню

Project/Options/Compiler

среды

Delphi, либо

в

меню

Options/Compiler Турбо-среды.

Соседние файлы в папке крутые билеты по инфе

- #

- #

- #

- #

-

Программирование и отладка.

Отла́дка

— этап разработки компьютерной программы,

на котором обнаруживают, локализуют и

устраняют ошибки. Чтобы понять, где

возникла ошибка, приходится :

-

узнавать

текущие значения переменных; -

выяснять,

по какому пути выполнялась программа.

Существуют

две взаимодополняющие технологии

отладки.

-

Использование

отладчиков — программ, которые включают

в себя пользовательский интерфейс для

пошагового выполнения программы:

оператор за оператором, функция за

функцией, с остановками на некоторых

строках исходного кода или при достижении

определённого условия. -

Вывод

текущего состояния программы с помощью

расположенных в критических точках

программы операторов вывода — на экран,

принтер, громкоговоритель или в файл.

Вывод отладочных сведений в файл

называется журналированием.

Место

отладки в цикле разработки программы

Типичный

цикл разработки, за время жизни программы

многократно повторяющийся, выглядит

примерно так:

Программирование

— внесение в программу новой

функциональности, исправление ошибок

в имеющейся.

Тестирование

(ручное или автоматизированное;

программистом, тестером или пользователем;

«дымовое», в режиме чёрного ящика или

модульное…) — обнаружение факта ошибки.

Воспроизведение

ошибки — выяснение условий, при которых

ошибка случается. Это может оказаться

непростой задачей при программировании

параллельных процессов и при некоторых

необычных ошибках, известных как

гейзенбаги.

Отладка

— обнаружение причины ошибки.

Инструменты

отладки

Отладчик

представляет из себя программный

инструмент, позволяющий программисту

наблюдать за выполнением исследуемой

программы, останавливать и перезапускать

её, прогонять в замедленном темпе,

изменять значения в памяти и даже, в

некоторых случаях, возвращать назад по

времени.

Также

полезными инструментами в руках

программиста могут оказаться:

-

Профилировщики.

Они позволят определить сколько времени

выполняется тот или иной участок кода,

а анализ покрытия позволит выявить

неисполняемые участки кода. -

API

логгеры позволяют программисту отследить

взаимодействие программы и Windows API при

помощи записи сообщений Windows в лог. -

Дизассемблеры

позволят программисту посмотреть

ассемблерный код исполняемого файла -

Сниферы

помогут программисту проследить сетевой

трафик генерируемой программой -

Сниферы

аппаратных интерфейсов позволят увидеть

данные которыми обменивается система

и устройство. -

Логи

системы.

Использование

языков программирования высокого

уровня, таких как Java, обычно упрощает

отладку, поскольку содержат такие

средства как обработка исключений,

сильно облегчающие поиск источника

проблемы. В некоторых низкоуровневых

языках, таких как ассемблер, ошибки

могут приводить к незаметным проблемам

— например, повреждениям памяти или

утечкам памяти, и бывает довольно трудно

определить что стало первоначальной

причиной ошибки. В этих случаях, могут

потребоваться изощрённые приёмы и

средства отладки.

Инструменты,

снижающие потребность в отладке

Другое

направление — сделать, чтобы отладка

нужна была как можно реже. Для этого

применяются:

-

Контрактное

программирование — чтобы программист

подтверждал другим путём, что ему на

выходе нужно именно такое поведение

программы. В языках, в которых контрактного

программирования нет, используется

самопроверка программы в ключевых

точках. -

Модульное

тестирование — проверка поведения

программы по частям. -

Статический

анализ кода — проверка кода на стандартные

ошибки «по недосмотру». -

Высокая

культура программирования, в частности,

паттерны проектирования, соглашения

об именовании и прозрачное поведение

отдельных блоков кода — чтобы объявить

себе и другим, каким образом должна

вести себя та или иная функция. -

Широкое

использование проверенных внешних

библиотек.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

05.06.2015525.32 Кб244.docx

- #

- #

- #

- #

05.06.2015321.73 Кб125.docx

- #

- #

- #

- #

Отладка программы — один их самых сложных этапов разработки программного обеспечения, требующий глубокого знания:

•специфики управления используемыми техническими средствами,

•операционной системы,

•среды и языка программирования,

•реализуемых процессов,

•природы и специфики различных ошибок,

•методик отладки и соответствующих программных средств.

Отладка — это процесс локализации и исправления ошибок, обнаруженных при тестировании программного обеспечения. Локализацией называют процесс определения оператора программы, выполнение которого вызвало нарушение нормального вычислительного процесса. Доя исправления ошибки необходимо определить ее причину, т. е. определить оператор или фрагмент, содержащие ошибку. Причины ошибок могут быть как очевидны, так и очень глубоко скрыты.

Вцелом сложность отладки обусловлена следующими причинами:

•требует от программиста глубоких знаний специфики управления используемыми техническими средствами, операционной системы, среды и языка программирования, реализуемых процессов, природы и специфики различных ошибок, методик отладки и соответствующих программных средств;

•психологически дискомфортна, так как необходимо искать собственные ошибки и, как правило, в условиях ограниченного времени;

•возможно взаимовлияние ошибок в разных частях программы, например, за счет затирания области памяти одного модуля другим из-за ошибок адресации;

•отсутствуют четко сформулированные методики отладки.

Всоответствии с этапом обработки, на котором проявляются ошибки, различают (рис. 10.1):

синтаксические ошибки — ошибки, фиксируемые компилятором (транслятором, интерпретатором) при выполнении синтаксического и частично семантического анализа программы; ошибки компоновки — ошибки, обнаруженные компоновщиком (редактором связей) при объединении модулей программы;

ошибки выполнения — ошибки, обнаруженные операционной системой, аппаратными средствами или пользователем при выполнении программы.

Синтаксические ошибки. Синтаксические ошибки относят к группе самых простых, так как синтаксис языка, как правило, строго формализован, и ошибки сопровождаются развернутым комментарием с указанием ее местоположения. Определение причин таких ошибок, как правило, труда не составляет, и даже при нечетком знании правил языка за несколько прогонов удается удалить все ошибки данного типа.

Следует иметь в виду, что чем лучше формализованы правила синтаксиса языка, тем больше ошибок из общего количества может обнаружить компилятор и, соответственно, меньше ошибок будет обнаруживаться на следующих этапах. В связи с этим говорят о языках программирования с защищенным синтаксисом и с незащищенным синтаксисом. К первым, безусловно, можно отнести Pascal, имеющий очень простой и четко определенный синтаксис, хорошо проверяемый при компиляции программы, ко вторым — Си со всеми его модификациями. Чего стоит хотя бы возможность выполнения присваивания в условном операторе в Си, например:

if (c = n) x = 0; /* в данном случае не проверятся равенство с и n, а выполняется присваивание с значения n, после чего результат операции сравнивается с нулем, если программист хотел выполнить не присваивание, а сравнение, то эта ошибка будет обнаружена только на этапе выполнения при получении результатов, отличающихся от ожидаемых */

Ошибки компоновки. Ошибки компоновки, как следует из названия, связаны с проблемами,

обнаруженными при разрешении внешних ссылок. Например, предусмотрено обращение к подпрограмме другого модуля, а при объединении модулей данная подпрограмма не найдена или не стыкуются списки параметров. В большинстве случаев ошибки такого рода также удается быстро локализовать и устранить.

Ошибки выполнения. К самой непредсказуемой группе относятся ошибки выполнения. Прежде всего они могут иметь разную природу, и соответственно по-разному проявляться. Часть ошибок обнаруживается и документируется операционной системой. Выделяют четыре способа проявления таких ошибок:

• появление сообщения об ошибке, зафиксированной схемами контроля выполнения машинных команд, например, переполнении разрядной сетки, ситуации «деление на ноль», нарушении адресации и т. п.;

•появление сообщения об ошибке, обнаруженной операционной системой, например, нарушении защиты памяти, попытке записи на устройства, защищенные от записи, отсутствии файла с заданным именем и т. п.;

•«зависание» компьютера, как простое, когда удается завершить программу без перезагрузки операционной системы, так и «тяжелое», когда для продолжения работы необходима перезагрузка;

•несовпадение полученных результатов с ожидаемыми.

Примечание. Отметим, что, если ошибки этапа выполнения обнаруживает пользователь, то в двух первых случаях, получив соответствующее сообщение, пользователь в зависимости от своего характера, степени необходимости и опыта работы за компьютером, либо попробует понять, что произошло, ища свою вину, либо обратится за помощью, либо постарается никогда больше не иметь дела с этим продуктом. При «зависании» компьютера пользователь может даже не сразу понять, что происходит что-то не то, хотя его печальный опыт и заставляет волноваться каждый раз, когда компьютер не выдает быстрой реакции на введенную команду, что также целесообразно иметь в виду. Также опасны могут быть ситуации, при которых пользователь получает неправильные результаты и использует их в своей работе.

Причины ошибок выполнения очень разнообразны, а потому и локализация может оказаться крайне сложной. Все возможные причины ошибок можно разделить на следующие группы:

•неверное определение исходных данных,

•логические ошибки,

•накопление погрешностей результатов вычислений (рис. 10.2).

Н е в е р н о е о п р е д е л е н и е и с х о д н ы х д а н н ы х происходит, если возникают любые ошибки при выполнении операций ввода-вывода: ошибки передачи, ошибки преобразования, ошибки перезаписи и ошибки данных. Причем использование специальных технических средств и программирование с защитой от ошибок (см.§ 2.7) позволяет обнаружить и предотвратить только часть этих ошибок, о чем безусловно не следует забывать.

Л о г и ч е с к и е о ш и б к и имеют разную природу. Так они могут следовать из ошибок, допущенных при проектировании, например, при выборе методов, разработке алгоритмов или определении структуры классов, а могут быть непосредственно внесены при кодировании модуля.

Кпоследней группе относят:

ошибки некорректного использования переменных, например, неудачный выбор типов данных, использование переменных до их инициализации, использование индексов, выходящих за границы определения массивов, нарушения соответствия типов данных при использовании явного или неявного переопределения типа данных, расположенных в памяти при использовании нетипизированных переменных, открытых массивов, объединений, динамической памяти, адресной арифметики и т. п.;

ошибки вычислений, например, некорректные вычисления над неарифметическими переменными, некорректное использование целочисленной арифметики, некорректное преобразование типов данных в процессе вычислений, ошибки, связанные с незнанием приоритетов выполнения операций для арифметических и логических выражений, и т. п.;

ошибки межмодульного интерфейса, например, игнорирование системных соглашений, нарушение типов и последовательности при передачи параметров, несоблюдение единства единиц измерения формальных и фактических параметров, нарушение области действия локальных и глобальных переменных;

другие ошибки кодирования, например, неправильная реализация логики программы при кодировании, игнорирование особенностей или ограничений конкретного языка программирования.

На к о п л е н и е п о г р е ш н о с т е й результатов числовых вычислений возникает, например, при некорректном отбрасывании дробных цифр чисел, некорректном использовании приближенных методов вычислений, игнорировании ограничения разрядной сетки представления вещественных чисел в ЭВМ и т. п.

Все указанные выше причины возникновения ошибок следует иметь в виду в процессе отладки. Кроме того, сложность отладки увеличивается также вследствие влияния следующих факторов:

опосредованного проявления ошибок;

возможности взаимовлияния ошибок;

возможности получения внешне одинаковых проявлений разных ошибок;

отсутствия повторяемости проявлений некоторых ошибок от запуска к запуску – так называемые стохастические ошибки;

возможности устранения внешних проявлений ошибок в исследуемой ситуации при внесении некоторых изменений в программу, например, при включении в программу диагностических фрагментов может аннулироваться или измениться внешнее проявление ошибок;

написания отдельных частей программы разными программистами.

Методы отладки программного обеспечения

Отладка программы в любом случае предполагает обдумывание и логическое осмысление всей имеющейся информации об ошибке. Большинство ошибок можно обнаружить по косвенным признакам посредством тщательного анализа текстов программ и результатов тестирования без получения дополнительной информации. При этом используют различные методы:

ручного тестирования;

индукции;

дедукции;

обратного прослеживания.

Метод ручного тестирования. Это — самый простой и естественный способ данной группы. При обнаружении ошибки необходимо выполнить тестируемую программу вручную, используя тестовый набор, при работе с которым была обнаружена ошибка.

Метод очень эффективен, но не применим для больших программ, программ со сложными вычислениями и в тех случаях, когда ошибка связана с неверным представлением программиста о выполнении некоторых операций.

Данный метод часто используют как составную часть других методов отладки.

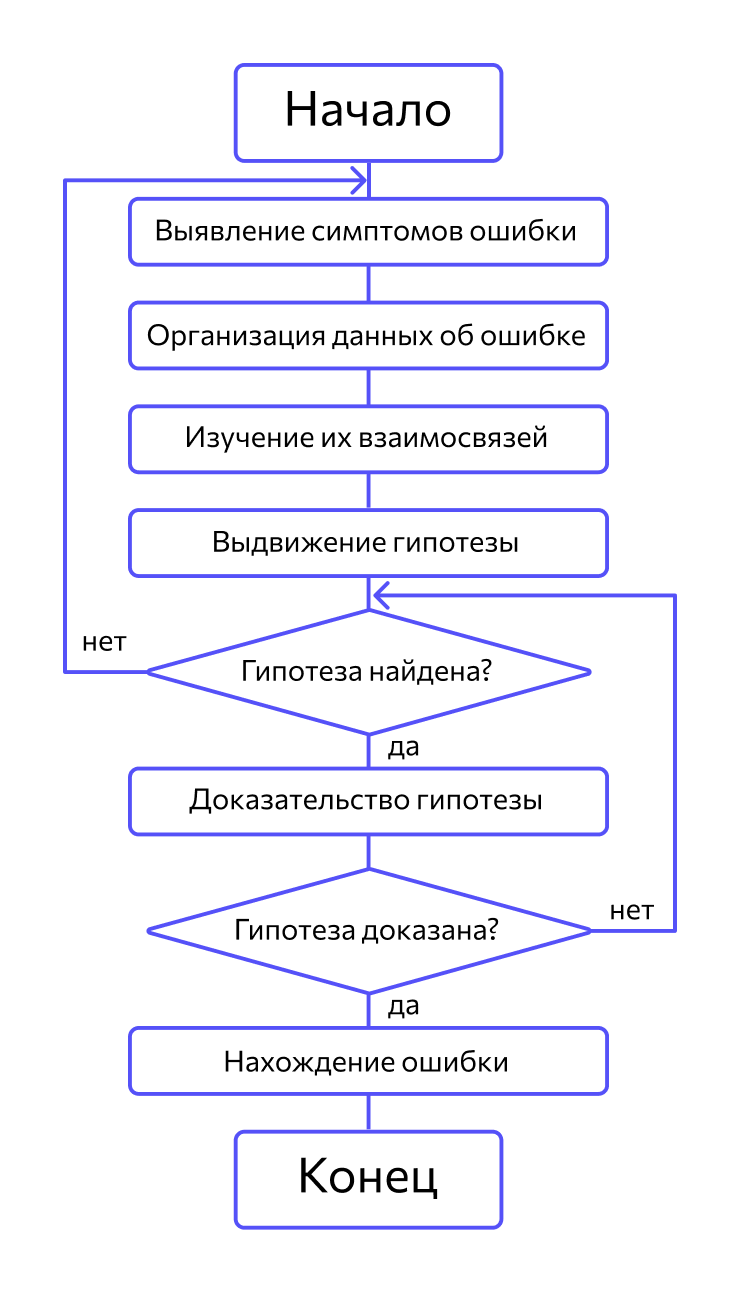

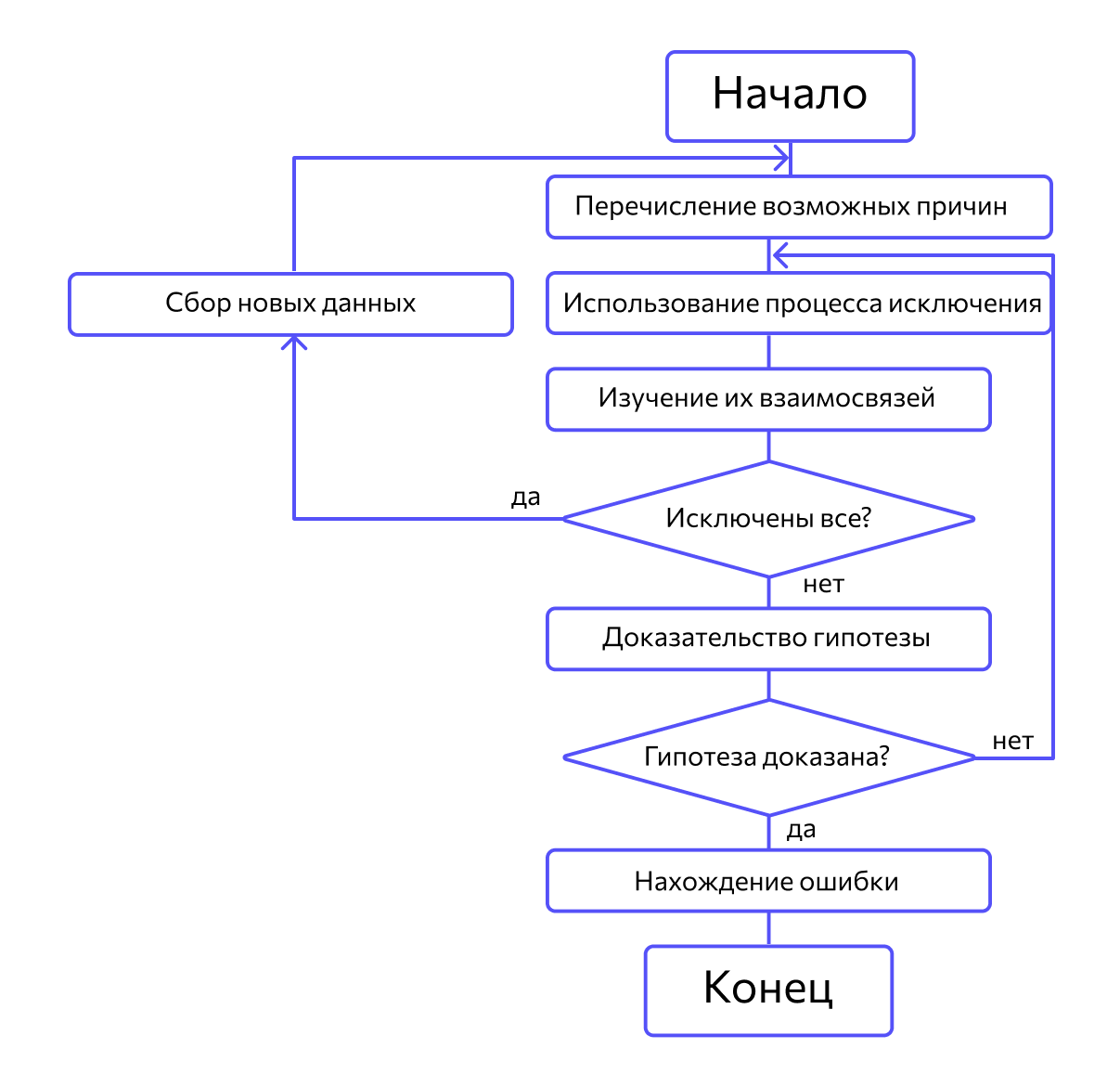

Метод индукции. Метод основан на тщательном анализе симптомов ошибки, которые могут проявляться как неверные результаты вычислений или как сообщение об ошибке. Если компьютер просто «зависает», то фрагмент проявления ошибки вычисляют, исходя из последних полученных результатов и действий пользователя. Полученную таким образом информацию организуют и тщательно изучают, просматривая соответствующий фрагмент программы. В результате этих действий выдвигают гипотезы об ошибках, каждую из которых проверяют. Если гипотеза верна, то детализируют информацию об ошибке, иначе — выдвигают другую гипотезу. Последовательность выполнения отладки методом индукции показана на рис. 10.3 в виде схемы алгоритма.

Самый ответственный этап — выявление симптомов ошибки. Организуя данные об ошибке, целесообразно записать все, что известно о ее проявлениях, причем фиксируют, как ситуации, в которых фрагмент с ошибкой выполняется нормально, так и ситуации, в которых ошибка проявляется. Если в результате изучения данных никаких гипотез не появляется, то необходима дополнительная информация об ошибке. Дополнительную информацию можно получить, например, в результате выполнения схожих тестов.

В процессе доказательства пытаются выяснить, все ли проявления ошибки объясняет данная гипотеза, если не все, то либо гипотеза не верна, либо ошибок несколько.

Метод дедукции. По методу дедукции вначале формируют множество причин, которые могли бы вызвать данное проявление ошибки. Затем анализируя причины, исключают те, которые противоречат имеющимся данным. Если все причины исключены, то следует выполнить дополнительное тестирование исследуемого фрагмента. В противном случае наиболее вероятную гипотезу пытаются доказать. Если гипотеза объясняет полученные признаки ошибки, то ошибка найдена, иначе — проверяют следующую причину (рис. 10.4).

Метод обратного прослеживания. Для небольших программ эффективно применение метода обратного прослеживания. Начинают с точки вывода неправильного результата. Для этой точки строится гипотеза о значениях основных переменных, которые могли бы привести к получению имеющегося результата. Далее, исходя из этой гипотезы, делают предложения о значениях переменных в предыдущей точке. Процесс продолжают, пока не обнаружат причину ошибки.

A software bug is an error, flaw or fault in the design, development, or operation of computer software that causes it to produce an incorrect or unexpected result, or to behave in unintended ways. The process of finding and correcting bugs is termed «debugging» and often uses formal techniques or tools to pinpoint bugs. Since the 1950s, some computer systems have been designed to deter, detect or auto-correct various computer bugs during operations.

Bugs in software can arise from mistakes and errors made in interpreting and extracting users’ requirements, planning a program’s design, writing its source code, and from interaction with humans, hardware and programs, such as operating systems or libraries. A program with many, or serious, bugs is often described as buggy. Bugs can trigger errors that may have ripple effects. The effects of bugs may be subtle, such as unintended text formatting, through to more obvious effects such as causing a program to crash, freezing the computer, or causing damage to hardware. Other bugs qualify as security bugs and might, for example, enable a malicious user to bypass access controls in order to obtain unauthorized privileges.[1]

Some software bugs have been linked to disasters. Bugs in code that controlled the Therac-25 radiation therapy machine were directly responsible for patient deaths in the 1980s. In 1996, the European Space Agency’s US$1 billion prototype Ariane 5 rocket was destroyed less than a minute after launch due to a bug in the on-board guidance computer program.[2] In 1994, an RAF Chinook helicopter crashed, killing 29; this was initially blamed on pilot error, but was later thought to have been caused by a software bug in the engine-control computer.[3] Buggy software caused the early 21st century British Post Office scandal, the most widespread miscarriage of justice in British legal history.[4]

In 2002, a study commissioned by the US Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology concluded that «software bugs, or errors, are so prevalent and so detrimental that they cost the US economy an estimated $59 billion annually, or about 0.6 percent of the gross domestic product».[5]

History[edit]

The Middle English word bugge is the basis for the terms «bugbear» and «bugaboo» as terms used for a monster.[6]

The term «bug» to describe defects has been a part of engineering jargon since the 1870s[7] and predates electronics and computers; it may have originally been used in hardware engineering to describe mechanical malfunctions. For instance, Thomas Edison wrote in a letter to an associate in 1878:[8]

… difficulties arise—this thing gives out and [it is] then that «Bugs»—as such little faults and difficulties are called—show themselves[9]

Baffle Ball, the first mechanical pinball game, was advertised as being «free of bugs» in 1931.[10] Problems with military gear during World War II were referred to as bugs (or glitches).[11] In a book published in 1942, Louise Dickinson Rich, speaking of a powered ice cutting machine, said, «Ice sawing was suspended until the creator could be brought in to take the bugs out of his darling.»[12]

Isaac Asimov used the term «bug» to relate to issues with a robot in his short story «Catch That Rabbit», published in 1944.

A page from the Harvard Mark II electromechanical computer’s log, featuring a dead moth that was removed from the device.

The term «bug» was used in an account by computer pioneer Grace Hopper, who publicized the cause of a malfunction in an early electromechanical computer.[13] A typical version of the story is:

In 1946, when Hopper was released from active duty, she joined the Harvard Faculty at the Computation Laboratory where she continued her work on the Mark II and Mark III. Operators traced an error in the Mark II to a moth trapped in a relay, coining the term bug. This bug was carefully removed and taped to the log book. Stemming from the first bug, today we call errors or glitches in a program a bug.[14]

Hopper was not present when the bug was found, but it became one of her favorite stories.[15] The date in the log book was September 9, 1947.[16][17][18] The operators who found it, including William «Bill» Burke, later of the Naval Weapons Laboratory, Dahlgren, Virginia,[19] were familiar with the engineering term and amusedly kept the insect with the notation «First actual case of bug being found.» This log book, complete with attached moth, is part of the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.[17]

The related term «debug» also appears to predate its usage in computing: the Oxford English Dictionary‘s etymology of the word contains an attestation from 1945, in the context of aircraft engines.[20]

The concept that software might contain errors dates back to Ada Lovelace’s 1843 notes on the analytical engine, in which she speaks of the possibility of program «cards» for Charles Babbage’s analytical engine being erroneous:

… an analysing process must equally have been performed in order to furnish the Analytical Engine with the necessary operative data; and that herein may also lie a possible source of error. Granted that the actual mechanism is unerring in its processes, the cards may give it wrong orders.

«Bugs in the System» report[edit]

The Open Technology Institute, run by the group, New America,[21] released a report «Bugs in the System» in August 2016 stating that U.S. policymakers should make reforms to help researchers identify and address software bugs. The report «highlights the need for reform in the field of software vulnerability discovery and disclosure.»[22] One of the report’s authors said that Congress has not done enough to address cyber software vulnerability, even though Congress has passed a number of bills to combat the larger issue of cyber security.[22]

Government researchers, companies, and cyber security experts are the people who typically discover software flaws. The report calls for reforming computer crime and copyright laws.[22]

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act criminalize and create civil penalties for actions that security researchers routinely engage in while conducting legitimate security research, the report said.[22]

Terminology[edit]

While the use of the term «bug» to describe software errors is common, many have suggested that it should be abandoned. One argument is that the word «bug» is divorced from a sense that a human being caused the problem, and instead implies that the defect arose on its own, leading to a push to abandon the term «bug» in favor of terms such as «defect», with limited success.[23] Since the 1970s Gary Kildall somewhat humorously suggested to use the term «blunder».[24][25]

In software engineering, mistake metamorphism (from Greek meta = «change», morph = «form») refers to the evolution of a defect in the final stage of software deployment. Transformation of a «mistake» committed by an analyst in the early stages of the software development lifecycle, which leads to a «defect» in the final stage of the cycle has been called ‘mistake metamorphism’.[26]

Different stages of a «mistake» in the entire cycle may be described as «mistakes», «anomalies», «faults», «failures», «errors», «exceptions», «crashes», «glitches», «bugs», «defects», «incidents», or «side effects».[26]

Prevention[edit]

The software industry has put much effort into reducing bug counts.[27][28] These include:

Typographical errors[edit]

Bugs usually appear when the programmer makes a logic error. Various innovations in programming style and defensive programming are designed to make these bugs less likely, or easier to spot. Some typos, especially of symbols or logical/mathematical operators, allow the program to operate incorrectly, while others such as a missing symbol or misspelled name may prevent the program from operating. Compiled languages can reveal some typos when the source code is compiled.

Development methodologies[edit]

Several schemes assist managing programmer activity so that fewer bugs are produced. Software engineering (which addresses software design issues as well) applies many techniques to prevent defects. For example, formal program specifications state the exact behavior of programs so that design bugs may be eliminated. Unfortunately, formal specifications are impractical for anything but the shortest programs, because of problems of combinatorial explosion and indeterminacy.

Unit testing involves writing a test for every function (unit) that a program is to perform.

In test-driven development unit tests are written before the code and the code is not considered complete until all tests complete successfully.

Agile software development involves frequent software releases with relatively small changes. Defects are revealed by user feedback.

Open source development allows anyone to examine source code. A school of thought popularized by Eric S. Raymond as Linus’s law says that popular open-source software has more chance of having few or no bugs than other software, because «given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow».[29] This assertion has been disputed, however: computer security specialist Elias Levy wrote that «it is easy to hide vulnerabilities in complex, little understood and undocumented source code,» because, «even if people are reviewing the code, that doesn’t mean they’re qualified to do so.»[30] An example of an open-source software bug was the 2008 OpenSSL vulnerability in Debian.

Programming language support[edit]

Programming languages include features to help prevent bugs, such as static type systems, restricted namespaces and modular programming. For example, when a programmer writes (pseudocode) LET REAL_VALUE PI = "THREE AND A BIT", although this may be syntactically correct, the code fails a type check. Compiled languages catch this without having to run the program. Interpreted languages catch such errors at runtime. Some languages deliberately exclude features that easily lead to bugs, at the expense of slower performance: the general principle being that, it is almost always better to write simpler, slower code than inscrutable code that runs slightly faster, especially considering that maintenance cost is substantial. For example, the Java programming language does not support pointer arithmetic; implementations of some languages such as Pascal and scripting languages often have runtime bounds checking of arrays, at least in a debugging build.

Code analysis[edit]

Tools for code analysis help developers by inspecting the program text beyond the compiler’s capabilities to spot potential problems. Although in general the problem of finding all programming errors given a specification is not solvable (see halting problem), these tools exploit the fact that human programmers tend to make certain kinds of simple mistakes often when writing software.

Instrumentation[edit]

Tools to monitor the performance of the software as it is running, either specifically to find problems such as bottlenecks or to give assurance as to correct working, may be embedded in the code explicitly (perhaps as simple as a statement saying PRINT "I AM HERE"), or provided as tools. It is often a surprise to find where most of the time is taken by a piece of code, and this removal of assumptions might cause the code to be rewritten.

Testing[edit]

Software testers are people whose primary task is to find bugs, or write code to support testing. On some projects, more resources may be spent on testing than in developing the program.

Measurements during testing can provide an estimate of the number of likely bugs remaining; this becomes more reliable the longer a product is tested and developed.[citation needed]

Debugging[edit]

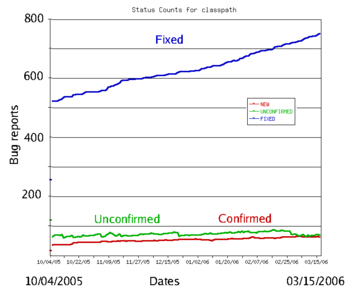

The typical bug history (GNU Classpath project data). A new bug submitted by the user is unconfirmed. Once it has been reproduced by a developer, it is a confirmed bug. The confirmed bugs are later fixed. Bugs belonging to other categories (unreproducible, will not be fixed, etc.) are usually in the minority

Finding and fixing bugs, or debugging, is a major part of computer programming. Maurice Wilkes, an early computing pioneer, described his realization in the late 1940s that much of the rest of his life would be spent finding mistakes in his own programs.[31]

Usually, the most difficult part of debugging is finding the bug. Once it is found, correcting it is usually relatively easy. Programs known as debuggers help programmers locate bugs by executing code line by line, watching variable values, and other features to observe program behavior. Without a debugger, code may be added so that messages or values may be written to a console or to a window or log file to trace program execution or show values.

However, even with the aid of a debugger, locating bugs is something of an art. It is not uncommon for a bug in one section of a program to cause failures in a completely different section,[citation needed] thus making it especially difficult to track (for example, an error in a graphics rendering routine causing a file I/O routine to fail), in an apparently unrelated part of the system.

Sometimes, a bug is not an isolated flaw, but represents an error of thinking or planning on the part of the programmer. Such logic errors require a section of the program to be overhauled or rewritten. As a part of code review, stepping through the code and imagining or transcribing the execution process may often find errors without ever reproducing the bug as such.

More typically, the first step in locating a bug is to reproduce it reliably. Once the bug is reproducible, the programmer may use a debugger or other tool while reproducing the error to find the point at which the program went astray.

Some bugs are revealed by inputs that may be difficult for the programmer to re-create. One cause of the Therac-25 radiation machine deaths was a bug (specifically, a race condition) that occurred only when the machine operator very rapidly entered a treatment plan; it took days of practice to become able to do this, so the bug did not manifest in testing or when the manufacturer attempted to duplicate it. Other bugs may stop occurring whenever the setup is augmented to help find the bug, such as running the program with a debugger; these are called heisenbugs (humorously named after the Heisenberg uncertainty principle).

Since the 1990s, particularly following the Ariane 5 Flight 501 disaster, interest in automated aids to debugging rose, such as static code analysis by abstract interpretation.[32]

Some classes of bugs have nothing to do with the code. Faulty documentation or hardware may lead to problems in system use, even though the code matches the documentation. In some cases, changes to the code eliminate the problem even though the code then no longer matches the documentation. Embedded systems frequently work around hardware bugs, since to make a new version of a ROM is much cheaper than remanufacturing the hardware, especially if they are commodity items.

Benchmark of bugs[edit]

To facilitate reproducible research on testing and debugging, researchers use curated benchmarks of bugs:

- the Siemens benchmark

- ManyBugs[33] is a benchmark of 185 C bugs in nine open-source programs.

- Defects4J[34] is a benchmark of 341 Java bugs from 5 open-source projects. It contains the corresponding patches, which cover a variety of patch type.

Bug management[edit]

Bug management includes the process of documenting, categorizing, assigning, reproducing, correcting and releasing the corrected code. Proposed changes to software – bugs as well as enhancement requests and even entire releases – are commonly tracked and managed using bug tracking systems or issue tracking systems.[35] The items added may be called defects, tickets, issues, or, following the agile development paradigm, stories and epics. Categories may be objective, subjective or a combination, such as version number, area of the software, severity and priority, as well as what type of issue it is, such as a feature request or a bug.

A bug triage reviews bugs and decides whether and when to fix them. The decision is based on the bug’s priority, and factors such as project schedules. The triage is not meant to investigate the cause of bugs, but rather the cost of fixing them. The triage happens regularly, and goes through bugs opened or reopened since the previous meeting. The attendees of the triage process typically are the project manager, development manager, test manager, build manager, and technical experts.[36][37]

Severity[edit]

Severity is the intensity of the impact the bug has on system operation.[38] This impact may be data loss, financial, loss of goodwill and wasted effort. Severity levels are not standardized. Impacts differ across industry. A crash in a video game has a totally different impact than a crash in a web browser, or real time monitoring system. For example, bug severity levels might be «crash or hang», «no workaround» (meaning there is no way the customer can accomplish a given task), «has workaround» (meaning the user can still accomplish the task), «visual defect» (for example, a missing image or displaced button or form element), or «documentation error». Some software publishers use more qualified severities such as «critical», «high», «low», «blocker» or «trivial».[39] The severity of a bug may be a separate category to its priority for fixing, and the two may be quantified and managed separately.

Priority[edit]

Priority controls where a bug falls on the list of planned changes. The priority is decided by each software producer. Priorities may be numerical, such as 1 through 5, or named, such as «critical», «high», «low», or «deferred». These rating scales may be similar or even identical to severity ratings, but are evaluated as a combination of the bug’s severity with its estimated effort to fix; a bug with low severity but easy to fix may get a higher priority than a bug with moderate severity that requires excessive effort to fix. Priority ratings may be aligned with product releases, such as «critical» priority indicating all the bugs that must be fixed before the next software release.

A bug severe enough to delay or halt the release of the product is called a «show stopper»[40] or «showstopper bug».[41] It is named so because it «stops the show» – causes unacceptable product failure.[41]

Software releases[edit]

It is common practice to release software with known, low-priority bugs. Bugs of sufficiently high priority may warrant a special release of part of the code containing only modules with those fixes. These are known as patches. Most releases include a mixture of behavior changes and multiple bug fixes. Releases that emphasize bug fixes are known as maintenance releases, to differentiate it from major releases that emphasize feature additions or changes.

Reasons that a software publisher opts not to patch or even fix a particular bug include:

- A deadline must be met and resources are insufficient to fix all bugs by the deadline.[42]

- The bug is already fixed in an upcoming release, and it is not of high priority.

- The changes required to fix the bug are too costly or affect too many other components, requiring a major testing activity.

- It may be suspected, or known, that some users are relying on the existing buggy behavior; a proposed fix may introduce a breaking change.

- The problem is in an area that will be obsolete with an upcoming release; fixing it is unnecessary.

- «It’s not a bug, it’s a feature».[43] A misunderstanding has arisen between expected and perceived behavior or undocumented feature.

Types[edit]

In software development projects, a mistake or error may be introduced at any stage. Bugs arise from oversight or misunderstanding by a software team during specification, design, coding, configuration, data entry or documentation. For example, a relatively simple program to alphabetize a list of words, the design might fail to consider what should happen when a word contains a hyphen. Or when converting an abstract design into code, the coder might inadvertently create an off-by-one error which can be a «<» where «<=» was intended, and fail to sort the last word in a list.

Another category of bug is called a race condition that may occur when programs have multiple components executing at the same time. If the components interact in a different order than the developer intended, they could interfere with each other and stop the program from completing its tasks. These bugs may be difficult to detect or anticipate, since they may not occur during every execution of a program.

Conceptual errors are a developer’s misunderstanding of what the software must do. The resulting software may perform according to the developer’s understanding, but not what is really needed. Other types:

Arithmetic[edit]

In operations on numerical values, problems can arise that result in unexpected output, slowing of a process, or crashing.[44] These can be from a lack of awareness of the qualities of the data storage such as a loss of precision due to rounding, numerically unstable algorithms, arithmetic overflow and underflow, or from lack of awareness of how calculations are handled by different software coding languages such as division by zero which in some languages may throw an exception, and in others may return a special value such as NaN or infinity.

Control flow[edit]

Control flow bugs are those found in processes with valid logic, but that lead to unintended results, such as infinite loops and infinite recursion, incorrect comparisons for conditional statements such as using the incorrect comparison operator, and off-by-one errors (counting one too many or one too few iterations when looping).

Interfacing[edit]

- Incorrect API usage.

- Incorrect protocol implementation.

- Incorrect hardware handling.

- Incorrect assumptions of a particular platform.

- Incompatible systems. A new API or communications protocol may seem to work when two systems use different versions, but errors may occur when a function or feature implemented in one version is changed or missing in another. In production systems which must run continually, shutting down the entire system for a major update may not be possible, such as in the telecommunication industry[45] or the internet.[46][47][48] In this case, smaller segments of a large system are upgraded individually, to minimize disruption to a large network. However, some sections could be overlooked and not upgraded, and cause compatibility errors which may be difficult to find and repair.

- Incorrect code annotations.

Concurrency[edit]

- Deadlock, where task A cannot continue until task B finishes, but at the same time, task B cannot continue until task A finishes.

- Race condition, where the computer does not perform tasks in the order the programmer intended.

- Concurrency errors in critical sections, mutual exclusions and other features of concurrent processing. Time-of-check-to-time-of-use (TOCTOU) is a form of unprotected critical section.

Resourcing[edit]

- Null pointer dereference.

- Using an uninitialized variable.

- Using an otherwise valid instruction on the wrong data type (see packed decimal/binary-coded decimal).

- Access violations.

- Resource leaks, where a finite system resource (such as memory or file handles) become exhausted by repeated allocation without release.

- Buffer overflow, in which a program tries to store data past the end of allocated storage. This may or may not lead to an access violation or storage violation. These are frequently security bugs.

- Excessive recursion which—though logically valid—causes stack overflow.

- Use-after-free error, where a pointer is used after the system has freed the memory it references.

- Double free error.

Syntax[edit]

- Use of the wrong token, such as performing assignment instead of equality test. For example, in some languages x=5 will set the value of x to 5 while x==5 will check whether x is currently 5 or some other number. Interpreted languages allow such code to fail. Compiled languages can catch such errors before testing begins.

Teamwork[edit]

- Unpropagated updates; e.g. programmer changes «myAdd» but forgets to change «mySubtract», which uses the same algorithm. These errors are mitigated by the Don’t Repeat Yourself philosophy.

- Comments out of date or incorrect: many programmers assume the comments accurately describe the code.

- Differences between documentation and product.

Implications[edit]

The amount and type of damage a software bug may cause naturally affects decision-making, processes and policy regarding software quality. In applications such as human spaceflight, aviation, nuclear power, health care, public transport or automotive safety, since software flaws have the potential to cause human injury or even death, such software will have far more scrutiny and quality control than, for example, an online shopping website. In applications such as banking, where software flaws have the potential to cause serious financial damage to a bank or its customers, quality control is also more important than, say, a photo editing application.

Other than the damage caused by bugs, some of their cost is due to the effort invested in fixing them. In 1978, Lientz et al. showed that the median of projects invest 17 percent of the development effort in bug fixing.[49] In research in 2020 on GitHub repositories showed the median is 20%.[50]

Residual bugs in delivered product[edit]

In 1994, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center managed to reduce their average number of errors from 4.5 per 1000 lines of code (SLOC) down to 1 per 1000 SLOC.[51]

Another study in 1990 reported that exceptionally good software development processes can achieve deployment failure rates as low as 0.1 per 1000 SLOC.[52] This figure is iterated in literature such as Code Complete by Steve McConnell,[53] and the NASA study on Flight Software Complexity.[54] Some projects even attained zero defects: the firmware in the IBM Wheelwriter typewriter which consists of 63,000 SLOC, and the Space Shuttle software with 500,000 SLOC.[52]

Well-known bugs[edit]

A number of software bugs have become well-known, usually due to their severity: examples include various space and military aircraft crashes. Possibly the most famous bug is the Year 2000 problem or Y2K bug, which caused many programs written long before the transition from 19xx to 20xx dates to malfunction, for example treating a date such as «25 Dec 04» as being in 1904, displaying «19100» instead of «2000», and so on. A huge effort at the end of the 20th century resolved the most severe problems, and there were no major consequences.

The 2012 stock trading disruption involved one such incompatibility between the old API and a new API.

In popular culture[edit]

- In both the 1968 novel 2001: A Space Odyssey and the corresponding 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, a spaceship’s onboard computer, HAL 9000, attempts to kill all its crew members. In the follow-up 1982 novel, 2010: Odyssey Two, and the accompanying 1984 film, 2010, it is revealed that this action was caused by the computer having been programmed with two conflicting objectives: to fully disclose all its information, and to keep the true purpose of the flight secret from the crew; this conflict caused HAL to become paranoid and eventually homicidal.

- In the English version of the Nena 1983 song 99 Luftballons (99 Red Balloons) as a result of «bugs in the software», a release of a group of 99 red balloons are mistaken for an enemy nuclear missile launch, requiring an equivalent launch response, resulting in catastrophe.

- In the 1999 American comedy Office Space, three employees attempt (unsuccessfully) to exploit their company’s preoccupation with the Y2K computer bug using a computer virus that sends rounded-off fractions of a penny to their bank account—a long-known technique described as salami slicing.

- The 2004 novel The Bug, by Ellen Ullman, is about a programmer’s attempt to find an elusive bug in a database application.[55]

- The 2008 Canadian film Control Alt Delete is about a computer programmer at the end of 1999 struggling to fix bugs at his company related to the year 2000 problem.

See also[edit]

- Anti-pattern

- Bug bounty program

- Glitch removal

- Hardware bug

- ISO/IEC 9126, which classifies a bug as either a defect or a nonconformity

- Orthogonal Defect Classification

- Racetrack problem

- RISKS Digest

- Software defect indicator

- Software regression

- Software rot

- Automatic bug fixing

References[edit]

- ^ Mittal, Varun; Aditya, Shivam (January 1, 2015). «Recent Developments in the Field of Bug Fixing». Procedia Computer Science. International Conference on Computer, Communication and Convergence (ICCC 2015). 48: 288–297. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2015.04.184. ISSN 1877-0509.

- ^ «Ariane 501 — Presentation of Inquiry Board report». www.esa.int. Retrieved January 29, 2022.

- ^ Prof. Simon Rogerson. «The Chinook Helicopter Disaster». Ccsr.cse.dmu.ac.uk. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ «Post Office scandal ruined lives, inquiry hears». BBC News. February 14, 2022.

- ^ «Software bugs cost US economy dear». June 10, 2009. Archived from the original on June 10, 2009. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Computerworld staff (September 3, 2011). «Moth in the machine: Debugging the origins of ‘bug’«. Computerworld. Archived from the original on August 25, 2015.

- ^ «bug». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) 5a

- ^ «Did You Know? Edison Coined the Term «Bug»«. August 1, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- ^ Edison to Puskas, 13 November 1878, Edison papers, Edison National Laboratory, U.S. National Park Service, West Orange, N.J., cited in Hughes, Thomas Parke (1989). American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm, 1870-1970. Penguin Books. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-14-009741-2.

- ^ «Baffle Ball». Internet Pinball Database.

(See image of advertisement in reference entry)

- ^ «Modern Aircraft Carriers are Result of 20 Years of Smart Experimentation». Life. June 29, 1942. p. 25. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Dickinson Rich, Louise (1942), We Took to the Woods, JB Lippincott Co, p. 93, LCCN 42024308, OCLC 405243, archived from the original on March 16, 2017.

- ^ FCAT NRT Test, Harcourt, March 18, 2008

- ^ «Danis, Sharron Ann: «Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper»«. ei.cs.vt.edu. February 16, 1997. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ James S. Huggins. «First Computer Bug». Jamesshuggins.com. Archived from the original on August 16, 2000. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ «Bug Archived March 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine», The Jargon File, ver. 4.4.7. Retrieved June 3, 2010.

- ^ a b «Log Book With Computer Bug Archived March 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine», National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ «The First «Computer Bug», Naval Historical Center. But note the Harvard Mark II computer was not complete until the summer of 1947.

- ^ IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol 22 Issue 1, 2000

- ^ Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society. 49, 183/2, 1945 «It ranged … through the stage of type test and flight test and ‘debugging’ …»

- ^ Wilson, Andi; Schulman, Ross; Bankston, Kevin; Herr, Trey. «Bugs in the System» (PDF). Open Policy Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Rozens, Tracy (August 12, 2016). «Cyber reforms needed to strengthen software bug discovery and disclosure: New America report – Homeland Preparedness News». Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- ^ «News at SEI 1999 Archive». cmu.edu. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013.

- ^ Shustek, Len (August 2, 2016). «In His Own Words: Gary Kildall». Remarkable People. Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on December 17, 2016.

- ^ Kildall, Gary Arlen (August 2, 2016) [1993]. Kildall, Scott; Kildall, Kristin (eds.). «Computer Connections: People, Places, and Events in the Evolution of the Personal Computer Industry» (Manuscript, part 1). Kildall Family: 14–15. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ a b «Testing experience : te : the magazine for professional testers». Testing Experience. Germany: testingexperience: 42. March 2012. ISSN 1866-5705. (subscription required)

- ^ Huizinga, Dorota; Kolawa, Adam (2007). Automated Defect Prevention: Best Practices in Software Management. Wiley-IEEE Computer Society Press. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-470-04212-0. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012.

- ^ McDonald, Marc; Musson, Robert; Smith, Ross (2007). The Practical Guide to Defect Prevention. Microsoft Press. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-7356-2253-1.

- ^ «Release Early, Release Often» Archived May 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Eric S. Raymond, The Cathedral and the Bazaar

- ^ «Wide Open Source» Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Elias Levy, SecurityFocus, April 17, 2000

- ^ Maurice Wilkes Quotes

- ^ «PolySpace Technologies history». christele.faure.pagesperso-orange.fr. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ Le Goues, Claire; Holtschulte, Neal; Smith, Edward K.; Brun, Yuriy; Devanbu, Premkumar; Forrest, Stephanie; Weimer, Westley (2015). «The ManyBugs and IntroClass Benchmarks for Automated Repair of C Programs». IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering. 41 (12): 1236–1256. doi:10.1109/TSE.2015.2454513. ISSN 0098-5589.

- ^ Just, René; Jalali, Darioush; Ernst, Michael D. (2014). «Defects4J: a database of existing faults to enable controlled testing studies for Java programs». Proceedings of the 2014 International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis — ISSTA 2014. pp. 437–440. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.646.3086. doi:10.1145/2610384.2628055. ISBN 9781450326452. S2CID 12796895.

- ^ Allen, Mitch (May–June 2002). «Bug Tracking Basics: A beginner’s guide to reporting and tracking defects». Software Testing & Quality Engineering Magazine. Vol. 4, no. 3. pp. 20–24. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ Rex Black (2002). Managing The Testing Process (2Nd Ed.). Wiley India Pvt. Limited. p. 139. ISBN 9788126503131. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ Chris Vander Mey (August 24, 2012). Shipping Greatness — Practical Lessons on Building and Launching Outstanding Software, Learned on the Job at Google and Amazon. O’Reilly Media. pp. 79–81. ISBN 9781449336608.

- ^ Soleimani Neysiani, Behzad; Babamir, Seyed Morteza; Aritsugi, Masayoshi (October 1, 2020). «Efficient feature extraction model for validation performance improvement of duplicate bug report detection in software bug triage systems». Information and Software Technology. 126: 106344. doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2020.106344. S2CID 219733047.

- ^ «5.3. Anatomy of a Bug». bugzilla.org. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013.

- ^ Jones, Wilbur D. Jr., ed. (1989). «Show stopper». Glossary: defense acquisition acronyms and terms (4 ed.). Fort Belvoir, Virginia, USA: Department of Defense, Defense Systems Management College. p. 123. hdl:2027/mdp.39015061290758 – via Hathitrust.

- ^ a b Zachary, G. Pascal (1994). Show-stopper!: the breakneck race to create Windows NT and the next generation at Microsoft. New York: The Free Press. p. 158. ISBN 0029356717 – via archive.org.

- ^ «The Next Generation 1996 Lexicon A to Z: Slipstream Release». Next Generation. No. 15. March 1996. p. 41.

- ^ Carr, Nicholas (2018). «‘It’s Not a Bug, It’s a Feature.’ Trite—or Just Right?». wired.com.

- ^ Di Franco, Anthony; Guo, Hui; Cindy, Rubio-González. «A Comprehensive Study of Real-World Numerical Bug Characteristics» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ Kimbler, K. (1998). Feature Interactions in Telecommunications and Software Systems V. IOS Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-90-5199-431-5.

- ^ Syed, Mahbubur Rahman (July 1, 2001). Multimedia Networking: Technology, Management and Applications: Technology, Management and Applications. Idea Group Inc (IGI). p. 398. ISBN 978-1-59140-005-9.

- ^ Wu, Chwan-Hwa (John); Irwin, J. David (April 19, 2016). Introduction to Computer Networks and Cybersecurity. CRC Press. p. 500. ISBN 978-1-4665-7214-0.

- ^ RFC 1263: «TCP Extensions Considered Harmful» quote: «the time to distribute the new version of the protocol to all hosts can be quite long (forever in fact). … If there is the slightest incompatibly between old and new versions, chaos can result.»

- ^ Lientz, B. P.; Swanson, E. B.; Tompkins, G. E. (1978). «Characteristics of Application Software Maintenance». Communications of the ACM. 21 (6): 466–471. doi:10.1145/359511.359522. S2CID 14950091.

- ^ Amit, Idan; Feitelson, Dror G. (2020). «The Corrective Commit Probability Code Quality Metric». arXiv:2007.10912 [cs.SE].

- ^ An overview of the Software Engineering Laboratory (PDF) (Report). Maryland, USA: Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA. December 1, 1994. pp41–42 Figure 18; pp43–44 Figure 21. CR-189410; SEL-94-005. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 22, 2022. Retrieved November 22, 2022. (bibliography: An overview of the Software Engineering Laboratory)

- ^ a b Cobb, Richard H.; Mills, Harlan D. (1990). «Engineering software under statistical quality control». IEEE Software. 7 (6): 46. doi:10.1109/52.60601. ISSN 1937-4194. S2CID 538311 – via University of Tennessee – Harlan D. Mills Collection.

- ^ McConnell, Steven C. (1993). Code Complete. Redmond, Washington, USA: Microsoft Press. p. 611. ISBN 9781556154843 – via archive.org.

(Cobb and Mills 1990)

- ^ Holzmann, Gerard (March 6, 2009). «Appendix D – Software Complexity» (PDF). In Dvorak, Daniel L. (ed.). NASA Study on Flight Software Complexity (Report). NASA. pdf frame 109/264. Appendix D p.2. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2022. Retrieved November 22, 2022. (under NASA Office of the Chief Engineer Technical Excellence Initiative)

- ^ Ullman, Ellen (2004). The Bug. Picador. ISBN 978-1-250-00249-5.

External links[edit]

- «Common Weakness Enumeration» – an expert webpage focus on bugs, at NIST.gov

- BUG type of Jim Gray – another Bug type

- Picture of the «first computer bug» at the Wayback Machine (archived January 12, 2015)

- «The First Computer Bug!» – an email from 1981 about Adm. Hopper’s bug

- «Toward Understanding Compiler Bugs in GCC and LLVM». A 2016 study of bugs in compilers

A software bug is an error, flaw or fault in the design, development, or operation of computer software that causes it to produce an incorrect or unexpected result, or to behave in unintended ways. The process of finding and correcting bugs is termed «debugging» and often uses formal techniques or tools to pinpoint bugs. Since the 1950s, some computer systems have been designed to deter, detect or auto-correct various computer bugs during operations.

Bugs in software can arise from mistakes and errors made in interpreting and extracting users’ requirements, planning a program’s design, writing its source code, and from interaction with humans, hardware and programs, such as operating systems or libraries. A program with many, or serious, bugs is often described as buggy. Bugs can trigger errors that may have ripple effects. The effects of bugs may be subtle, such as unintended text formatting, through to more obvious effects such as causing a program to crash, freezing the computer, or causing damage to hardware. Other bugs qualify as security bugs and might, for example, enable a malicious user to bypass access controls in order to obtain unauthorized privileges.[1]

Some software bugs have been linked to disasters. Bugs in code that controlled the Therac-25 radiation therapy machine were directly responsible for patient deaths in the 1980s. In 1996, the European Space Agency’s US$1 billion prototype Ariane 5 rocket was destroyed less than a minute after launch due to a bug in the on-board guidance computer program.[2] In 1994, an RAF Chinook helicopter crashed, killing 29; this was initially blamed on pilot error, but was later thought to have been caused by a software bug in the engine-control computer.[3] Buggy software caused the early 21st century British Post Office scandal, the most widespread miscarriage of justice in British legal history.[4]

In 2002, a study commissioned by the US Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology concluded that «software bugs, or errors, are so prevalent and so detrimental that they cost the US economy an estimated $59 billion annually, or about 0.6 percent of the gross domestic product».[5]

History[edit]

The Middle English word bugge is the basis for the terms «bugbear» and «bugaboo» as terms used for a monster.[6]

The term «bug» to describe defects has been a part of engineering jargon since the 1870s[7] and predates electronics and computers; it may have originally been used in hardware engineering to describe mechanical malfunctions. For instance, Thomas Edison wrote in a letter to an associate in 1878:[8]

… difficulties arise—this thing gives out and [it is] then that «Bugs»—as such little faults and difficulties are called—show themselves[9]

Baffle Ball, the first mechanical pinball game, was advertised as being «free of bugs» in 1931.[10] Problems with military gear during World War II were referred to as bugs (or glitches).[11] In a book published in 1942, Louise Dickinson Rich, speaking of a powered ice cutting machine, said, «Ice sawing was suspended until the creator could be brought in to take the bugs out of his darling.»[12]

Isaac Asimov used the term «bug» to relate to issues with a robot in his short story «Catch That Rabbit», published in 1944.

A page from the Harvard Mark II electromechanical computer’s log, featuring a dead moth that was removed from the device.

The term «bug» was used in an account by computer pioneer Grace Hopper, who publicized the cause of a malfunction in an early electromechanical computer.[13] A typical version of the story is:

In 1946, when Hopper was released from active duty, she joined the Harvard Faculty at the Computation Laboratory where she continued her work on the Mark II and Mark III. Operators traced an error in the Mark II to a moth trapped in a relay, coining the term bug. This bug was carefully removed and taped to the log book. Stemming from the first bug, today we call errors or glitches in a program a bug.[14]

Hopper was not present when the bug was found, but it became one of her favorite stories.[15] The date in the log book was September 9, 1947.[16][17][18] The operators who found it, including William «Bill» Burke, later of the Naval Weapons Laboratory, Dahlgren, Virginia,[19] were familiar with the engineering term and amusedly kept the insect with the notation «First actual case of bug being found.» This log book, complete with attached moth, is part of the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.[17]

The related term «debug» also appears to predate its usage in computing: the Oxford English Dictionary‘s etymology of the word contains an attestation from 1945, in the context of aircraft engines.[20]

The concept that software might contain errors dates back to Ada Lovelace’s 1843 notes on the analytical engine, in which she speaks of the possibility of program «cards» for Charles Babbage’s analytical engine being erroneous:

… an analysing process must equally have been performed in order to furnish the Analytical Engine with the necessary operative data; and that herein may also lie a possible source of error. Granted that the actual mechanism is unerring in its processes, the cards may give it wrong orders.

«Bugs in the System» report[edit]

The Open Technology Institute, run by the group, New America,[21] released a report «Bugs in the System» in August 2016 stating that U.S. policymakers should make reforms to help researchers identify and address software bugs. The report «highlights the need for reform in the field of software vulnerability discovery and disclosure.»[22] One of the report’s authors said that Congress has not done enough to address cyber software vulnerability, even though Congress has passed a number of bills to combat the larger issue of cyber security.[22]

Government researchers, companies, and cyber security experts are the people who typically discover software flaws. The report calls for reforming computer crime and copyright laws.[22]

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act criminalize and create civil penalties for actions that security researchers routinely engage in while conducting legitimate security research, the report said.[22]

Terminology[edit]

While the use of the term «bug» to describe software errors is common, many have suggested that it should be abandoned. One argument is that the word «bug» is divorced from a sense that a human being caused the problem, and instead implies that the defect arose on its own, leading to a push to abandon the term «bug» in favor of terms such as «defect», with limited success.[23] Since the 1970s Gary Kildall somewhat humorously suggested to use the term «blunder».[24][25]

In software engineering, mistake metamorphism (from Greek meta = «change», morph = «form») refers to the evolution of a defect in the final stage of software deployment. Transformation of a «mistake» committed by an analyst in the early stages of the software development lifecycle, which leads to a «defect» in the final stage of the cycle has been called ‘mistake metamorphism’.[26]

Different stages of a «mistake» in the entire cycle may be described as «mistakes», «anomalies», «faults», «failures», «errors», «exceptions», «crashes», «glitches», «bugs», «defects», «incidents», or «side effects».[26]

Prevention[edit]

The software industry has put much effort into reducing bug counts.[27][28] These include:

Typographical errors[edit]

Bugs usually appear when the programmer makes a logic error. Various innovations in programming style and defensive programming are designed to make these bugs less likely, or easier to spot. Some typos, especially of symbols or logical/mathematical operators, allow the program to operate incorrectly, while others such as a missing symbol or misspelled name may prevent the program from operating. Compiled languages can reveal some typos when the source code is compiled.

Development methodologies[edit]

Several schemes assist managing programmer activity so that fewer bugs are produced. Software engineering (which addresses software design issues as well) applies many techniques to prevent defects. For example, formal program specifications state the exact behavior of programs so that design bugs may be eliminated. Unfortunately, formal specifications are impractical for anything but the shortest programs, because of problems of combinatorial explosion and indeterminacy.

Unit testing involves writing a test for every function (unit) that a program is to perform.

In test-driven development unit tests are written before the code and the code is not considered complete until all tests complete successfully.

Agile software development involves frequent software releases with relatively small changes. Defects are revealed by user feedback.

Open source development allows anyone to examine source code. A school of thought popularized by Eric S. Raymond as Linus’s law says that popular open-source software has more chance of having few or no bugs than other software, because «given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow».[29] This assertion has been disputed, however: computer security specialist Elias Levy wrote that «it is easy to hide vulnerabilities in complex, little understood and undocumented source code,» because, «even if people are reviewing the code, that doesn’t mean they’re qualified to do so.»[30] An example of an open-source software bug was the 2008 OpenSSL vulnerability in Debian.

Programming language support[edit]

Programming languages include features to help prevent bugs, such as static type systems, restricted namespaces and modular programming. For example, when a programmer writes (pseudocode) LET REAL_VALUE PI = "THREE AND A BIT", although this may be syntactically correct, the code fails a type check. Compiled languages catch this without having to run the program. Interpreted languages catch such errors at runtime. Some languages deliberately exclude features that easily lead to bugs, at the expense of slower performance: the general principle being that, it is almost always better to write simpler, slower code than inscrutable code that runs slightly faster, especially considering that maintenance cost is substantial. For example, the Java programming language does not support pointer arithmetic; implementations of some languages such as Pascal and scripting languages often have runtime bounds checking of arrays, at least in a debugging build.

Code analysis[edit]

Tools for code analysis help developers by inspecting the program text beyond the compiler’s capabilities to spot potential problems. Although in general the problem of finding all programming errors given a specification is not solvable (see halting problem), these tools exploit the fact that human programmers tend to make certain kinds of simple mistakes often when writing software.

Instrumentation[edit]

Tools to monitor the performance of the software as it is running, either specifically to find problems such as bottlenecks or to give assurance as to correct working, may be embedded in the code explicitly (perhaps as simple as a statement saying PRINT "I AM HERE"), or provided as tools. It is often a surprise to find where most of the time is taken by a piece of code, and this removal of assumptions might cause the code to be rewritten.

Testing[edit]

Software testers are people whose primary task is to find bugs, or write code to support testing. On some projects, more resources may be spent on testing than in developing the program.

Measurements during testing can provide an estimate of the number of likely bugs remaining; this becomes more reliable the longer a product is tested and developed.[citation needed]

Debugging[edit]

The typical bug history (GNU Classpath project data). A new bug submitted by the user is unconfirmed. Once it has been reproduced by a developer, it is a confirmed bug. The confirmed bugs are later fixed. Bugs belonging to other categories (unreproducible, will not be fixed, etc.) are usually in the minority

Finding and fixing bugs, or debugging, is a major part of computer programming. Maurice Wilkes, an early computing pioneer, described his realization in the late 1940s that much of the rest of his life would be spent finding mistakes in his own programs.[31]

Usually, the most difficult part of debugging is finding the bug. Once it is found, correcting it is usually relatively easy. Programs known as debuggers help programmers locate bugs by executing code line by line, watching variable values, and other features to observe program behavior. Without a debugger, code may be added so that messages or values may be written to a console or to a window or log file to trace program execution or show values.

However, even with the aid of a debugger, locating bugs is something of an art. It is not uncommon for a bug in one section of a program to cause failures in a completely different section,[citation needed] thus making it especially difficult to track (for example, an error in a graphics rendering routine causing a file I/O routine to fail), in an apparently unrelated part of the system.

Sometimes, a bug is not an isolated flaw, but represents an error of thinking or planning on the part of the programmer. Such logic errors require a section of the program to be overhauled or rewritten. As a part of code review, stepping through the code and imagining or transcribing the execution process may often find errors without ever reproducing the bug as such.

More typically, the first step in locating a bug is to reproduce it reliably. Once the bug is reproducible, the programmer may use a debugger or other tool while reproducing the error to find the point at which the program went astray.

Some bugs are revealed by inputs that may be difficult for the programmer to re-create. One cause of the Therac-25 radiation machine deaths was a bug (specifically, a race condition) that occurred only when the machine operator very rapidly entered a treatment plan; it took days of practice to become able to do this, so the bug did not manifest in testing or when the manufacturer attempted to duplicate it. Other bugs may stop occurring whenever the setup is augmented to help find the bug, such as running the program with a debugger; these are called heisenbugs (humorously named after the Heisenberg uncertainty principle).

Since the 1990s, particularly following the Ariane 5 Flight 501 disaster, interest in automated aids to debugging rose, such as static code analysis by abstract interpretation.[32]

Some classes of bugs have nothing to do with the code. Faulty documentation or hardware may lead to problems in system use, even though the code matches the documentation. In some cases, changes to the code eliminate the problem even though the code then no longer matches the documentation. Embedded systems frequently work around hardware bugs, since to make a new version of a ROM is much cheaper than remanufacturing the hardware, especially if they are commodity items.

Benchmark of bugs[edit]

To facilitate reproducible research on testing and debugging, researchers use curated benchmarks of bugs:

- the Siemens benchmark

- ManyBugs[33] is a benchmark of 185 C bugs in nine open-source programs.