Thought I would just report back my findings, now that I have it all working. The following client-side code (slightly abridged and anonymized) contains all the work-arounds I needed to address the prblems outlined in this thread and works on IE (8.0.6001), FF(3.5.9), and Chrome (5.0.375.55 beta). Still yet to test under older versions of browsers. Many thanks to all who responded.

I should also add that I needed to make sure that the server response needed to include:

Response.ContentType = "text/xml" ;

for it to work with IE. FF didn’t mind if the ContentType was text/HTML but IE coughed.

Code to create an XMLHTTP request:

function GetXMLHTTPRequest ()

{

var activexmodes=["Msxml2.XMLHTTP", "Microsoft.XMLHTTP"] ; //activeX versions to check for in IE

if (window.ActiveXObject) //Test for support for ActiveXObject in IE first (as XMLHttpRequest in IE7 is broken)

{

for (var i=0; i < activexmodes.length ; i++)

{

try

{

return new ActiveXObject(activexmodes[i]) ;

}

catch (e)

{ //suppress error

}

}

}

else if (window.XMLHttpRequest) // if Mozilla, Safari etc

{

return new XMLHttpRequest () ;

}

else

{

return (false) ;

}

}

Code to return the text value of a record node:

function GetRecordElement (ARecordNode, AFieldName)

{

try

{

if (ARecordNode.getElementsByTagName (AFieldName) [0].textContent != undefined)

{

return (ARecordNode.getElementsByTagName (AFieldName) [0].textContent) ; // Chrome, FF

}

if (ARecordNode.getElementsByTagName (AFieldName) [0].text != undefined)

{

return (ARecordNode.getElementsByTagName (AFieldName) [0].text) ; // IE

}

return ("unknown") ;

}

catch (Exception)

{

ReportError ("(GetRecordElement): " + Exception.description) ;

}

}

Code to perform the AJAX request:

function GetRecord (s)

{

try

{

ReportStatus ("") ;

var xmlhttp = GetXMLHTTPRequest () ;

if (xmlhttp)

{

xmlhttp.open ("GET", "blahblah.com/AJAXget.asp?...etc", true) ;

if (xmlhttp.overrideMimeType)

{

xmlhttp.overrideMimeType("text/xml") ;

}

xmlhttp.setRequestHeader ("Content-Type", "text/xml; charset="utf-8"") ;

xmlhttp.onreadystatechange = function ()

{

if (xmlhttp.readyState == 4)

{

if (xmlhttp.responseXML != null)

{

var xmlDoc = xmlhttp.responseXML;

var ResultNodes = xmlDoc.getElementsByTagName ("Result") ;

if (ResultNodes != null)

{

var PayloadNode = xmlDoc.getElementsByTagName ("Payload") ;

if (PayloadNode != null)

{

var ResultText = ResultNodes [0].firstChild.nodeValue ;

if (ResultText == "OK")

{

ReportStatus (ResultText) ;

var RecordNode = PayloadNode [0].firstChild ;

if (RecordNode != null)

{

UpdateRecordDisplay (RecordNode) ; // eventually calls GetRecordElement

}

else

{

ReportError ("RecordNode is null") ;

}

}

else

{

ReportError ("Unknown response:" + ResultText) ;

}

}

else

{

ReportError ("PayloadNode is null") ;

}

}

else

{

ReportError ("ResultNodes is null") ;

}

}

else

{

ReportError ("responseXML is null") ;

}

}

else

{

ReportStatus ("Status=" + xmlhttp.readyState) ;

}

}

ReportStatus ("Requesting data ...") ;

xmlhttp.send (null) ;

}

else

{

ReportError ("Unable to create request") ;

}

}

catch (err)

{

ReportError ("(GetRecord): " + err.description) ;

}

}

In SQL, null or NULL is a special marker used to indicate that a data value does not exist in the database. Introduced by the creator of the relational database model, E. F. Codd, SQL null serves to fulfil the requirement that all true relational database management systems (RDBMS) support a representation of «missing information and inapplicable information». Codd also introduced the use of the lowercase Greek omega (ω) symbol to represent null in database theory. In SQL, NULL is a reserved word used to identify this marker.

A null should not be confused with a value of 0. A null value indicates a lack of a value, which is not the same thing as a value of zero. For example, consider the question «How many books does Adam own?» The answer may be «zero» (we know that he owns none) or «null» (we do not know how many he owns). In a database table, the column reporting this answer would start out with no value (marked by Null), and it would not be updated with the value «zero» until we have ascertained that Adam owns no books.

SQL null is a marker, not a value. This usage is quite different from most programming languages, where null value of a reference means it is not pointing to any object.

History[edit]

E. F. Codd mentioned nulls as a method of representing missing data in the relational model in a 1975 paper in the FDT Bulletin of ACM-SIGMOD. Codd’s paper that is most commonly cited in relation with the semantics of Null (as adopted in SQL) is his 1979 paper in the ACM Transactions on Database Systems, in which he also introduced his Relational Model/Tasmania, although much of the other proposals from the latter paper have remained obscure. Section 2.3 of his 1979 paper details the semantics of Null propagation in arithmetic operations as well as comparisons employing a ternary (three-valued) logic when comparing to nulls; it also details the treatment of Nulls on other set operations (the latter issue still controversial today). In database theory circles, the original proposal of Codd (1975, 1979) is now referred to as «Codd tables».[1] Codd later reinforced his requirement that all RDBMSs support Null to indicate missing data in a 1985 two-part article published in Computerworld magazine.[2][3]

The 1986 SQL standard basically adopted Codd’s proposal after an implementation prototype in IBM System R. Although Don Chamberlin recognized nulls (alongside duplicate rows) as one of the most controversial features of SQL, he defended the design of Nulls in SQL invoking the pragmatic arguments that it was the least expensive form of system support for missing information, saving the programmer from many duplicative application-level checks (see semipredicate problem) while at the same time providing the database designer with the option not to use Nulls if they so desire; for example, in order to avoid well known anomalies (discussed in the semantics section of this article). Chamberlin also argued that besides providing some missing-value functionality, practical experience with Nulls also led to other language features which rely on Nulls, like certain grouping constructs and outer joins. Finally, he argued that in practice Nulls also end up being used as a quick way to patch an existing schema when it needs to evolve beyond its original intent, coding not for missing but rather for inapplicable information; for example, a database that quickly needs to support electric cars while having a miles-per-gallon column.[4]

Codd indicated in his 1990 book The Relational Model for Database Management, Version 2 that the single Null mandated by the SQL standard was inadequate, and should be replaced by two separate Null-type markers to indicate the reason why data is missing. In Codd’s book, these two Null-type markers are referred to as ‘A-Values’ and ‘I-Values’, representing ‘Missing But Applicable’ and ‘Missing But Inapplicable’, respectively.[5] Codd’s recommendation would have required SQL’s logic system be expanded to accommodate a four-valued logic system. Because of this additional complexity, the idea of multiple Nulls with different definitions has not gained widespread acceptance in the database practitioners’ domain. It remains an active field of research though, with numerous papers still being published.

Challenges[edit]

Null has been the focus of controversy and a source of debate because of its associated three-valued logic (3VL), special requirements for its use in SQL joins, and the special handling required by aggregate functions and SQL grouping operators. Computer science professor Ron van der Meyden summarized the various issues as: «The inconsistencies in the SQL standard mean that it is not possible to ascribe any intuitive logical semantics to the treatment of nulls in SQL.»[1] Although various proposals have been made for resolving these issues, the complexity of the alternatives has prevented their widespread adoption.

Null propagation[edit]

Arithmetic operations[edit]

Because Null is not a data value, but a marker for an absent value, using mathematical operators on Null gives an unknown result, which is represented by Null.[6] In the following example, multiplying 10 by Null results in Null:

10 * NULL -- Result is NULL

This can lead to unanticipated results. For instance, when an attempt is made to divide Null by zero, platforms may return Null instead of throwing an expected «data exception – division by zero».[6] Though this behavior is not defined by the ISO SQL standard many DBMS vendors treat this operation similarly. For instance, the Oracle, PostgreSQL, MySQL Server, and Microsoft SQL Server platforms all return a Null result for the following:

String concatenation[edit]

String concatenation operations, which are common in SQL, also result in Null when one of the operands is Null.[7] The following example demonstrates the Null result returned by using Null with the SQL || string concatenation operator.

'Fish ' || NULL || 'Chips' -- Result is NULL

This is not true for all database implementations. In an Oracle RDBMS for example NULL and the empty string are considered the same thing and therefore ‘Fish ‘ || NULL || ‘Chips’ results in ‘Fish Chips’.

Comparisons with NULL and the three-valued logic (3VL)[edit]

Since Null is not a member of any data domain, it is not considered a «value», but rather a marker (or placeholder) indicating the undefined value. Because of this, comparisons with Null can never result in either True or False, but always in a third logical result, Unknown.[8] The logical result of the expression below, which compares the value 10 to Null, is Unknown:

SELECT 10 = NULL -- Results in Unknown

However, certain operations on Null can return values if the absent value is not relevant to the outcome of the operation. Consider the following example:

SELECT NULL OR TRUE -- Results in True

In this case, the fact that the value on the left of OR is unknowable is irrelevant, because the outcome of the OR operation would be True regardless of the value on the left.

SQL implements three logical results, so SQL implementations must provide for a specialized three-valued logic (3VL). The rules governing SQL three-valued logic are shown in the tables below (p and q represent logical states)»[9] The truth tables SQL uses for AND, OR, and NOT correspond to a common fragment of the Kleene and Łukasiewicz three-valued logic (which differ in their definition of implication, however SQL defines no such operation).[10]

| p | q | p OR q | p AND q | p = q |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | True | True | True | True |

| True | False | True | False | False |

| True | Unknown | True | Unknown | Unknown |

| False | True | True | False | False |

| False | False | False | False | True |

| False | Unknown | Unknown | False | Unknown |

| Unknown | True | True | Unknown | Unknown |

| Unknown | False | Unknown | False | Unknown |

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| p | NOT p |

|---|---|

| True | False |

| False | True |

| Unknown | Unknown |

Effect of Unknown in WHERE clauses[edit]

SQL three-valued logic is encountered in Data Manipulation Language (DML) in comparison predicates of DML statements and queries. The WHERE clause causes the DML statement to act on only those rows for which the predicate evaluates to True. Rows for which the predicate evaluates to either False or Unknown are not acted on by INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE DML statements, and are discarded by SELECT queries. Interpreting Unknown and False as the same logical result is a common error encountered while dealing with Nulls.[9] The following simple example demonstrates this fallacy:

SELECT * FROM t WHERE i = NULL;

The example query above logically always returns zero rows because the comparison of the i column with Null always returns Unknown, even for those rows where i is Null. The Unknown result causes the SELECT statement to summarily discard each and every row. (However, in practice, some SQL tools will retrieve rows using a comparison with Null.)

Null-specific and 3VL-specific comparison predicates[edit]

Basic SQL comparison operators always return Unknown when comparing anything with Null, so the SQL standard provides for two special Null-specific comparison predicates. The IS NULL and IS NOT NULL predicates (which use a postfix syntax) test whether data is, or is not, Null.[11]

The SQL standard contains the optional feature F571 «Truth value tests» that introduces three additional logical unary operators (six in fact, if we count their negation, which is part of their syntax), also using postfix notation. They have the following truth tables:[12]

| p | p IS TRUE | p IS NOT TRUE | p IS FALSE | p IS NOT FALSE | p IS UNKNOWN | p IS NOT UNKNOWN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | True | False | False | True | False | True |

| False | False | True | True | False | False | True |

| Unknown | False | True | False | True | True | False |

The F571 feature is orthogonal to the presence of the boolean datatype in SQL (discussed later in this article) and, despite syntactic similarities, F571 does not introduce boolean or three-valued literals in the language. The F571 feature was actually present in SQL92,[13] well before the boolean datatype was introduced to the standard in 1999. The F571 feature is implemented by few systems however; PostgreSQL is one of those implementing it.

The addition of IS UNKNOWN to the other operators of SQL’s three-valued logic makes the SQL three-valued logic functionally complete,[14] meaning its logical operators can express (in combination) any conceivable three-valued logical function.

On systems which don’t support the F571 feature, it is possible to emulate IS UNKNOWN p by going over every argument that could make the expression p Unknown and test those arguments with IS NULL or other NULL-specific functions, although this may be more cumbersome.

Law of the excluded fourth (in WHERE clauses)[edit]

In SQL’s three-valued logic the law of the excluded middle, p OR NOT p, no longer evaluates to true for all p. More precisely, in SQL’s three-valued logic p OR NOT p is unknown precisely when p is unknown and true otherwise. Because direct comparisons with Null result in the unknown logical value, the following query

SELECT * FROM stuff WHERE ( x = 10 ) OR NOT ( x = 10 );

is not equivalent in SQL with

if the column x contains any Nulls; in that case the second query would return some rows the first one does not return, namely all those in which x is Null. In classical two-valued logic, the law of the excluded middle would allow the simplification of the WHERE clause predicate, in fact its elimination. Attempting to apply the law of the excluded middle to SQL’s 3VL is effectively a false dichotomy. The second query is actually equivalent with:

SELECT * FROM stuff; -- is (because of 3VL) equivalent to: SELECT * FROM stuff WHERE ( x = 10 ) OR NOT ( x = 10 ) OR x IS NULL;

Thus, to correctly simplify the first statement in SQL requires that we return all rows in which x is not null.

SELECT * FROM stuff WHERE x IS NOT NULL;

In view of the above, observe that for SQL’s WHERE clause a tautology similar to the law of excluded middle can be written. Assuming the IS UNKNOWN operator is present, p OR (NOT p) OR (p IS UNKNOWN) is true for every predicate p. Among logicians, this is called law of excluded fourth.

There are some SQL expressions in which it is less obvious where the false dilemma occurs, for example:

SELECT 'ok' WHERE 1 NOT IN (SELECT CAST (NULL AS INTEGER)) UNION SELECT 'ok' WHERE 1 IN (SELECT CAST (NULL AS INTEGER));

produces no rows because IN translates to an iterated version of equality over the argument set and 1<>NULL is Unknown, just as a 1=NULL is Unknown. (The CAST in this example is needed only in some SQL implementations like PostgreSQL, which would reject it with a type checking error otherwise. In many systems plain SELECT NULL works in the subquery.) The missing case above is of course:

SELECT 'ok' WHERE (1 IN (SELECT CAST (NULL AS INTEGER))) IS UNKNOWN;

Effect of Null and Unknown in other constructs[edit]

Joins[edit]

Joins evaluate using the same comparison rules as for WHERE clauses. Therefore, care must be taken when using nullable columns in SQL join criteria. In particular a table containing any nulls is not equal with a natural self-join of itself, meaning that whereas

The SQL COALESCE function or CASE expressions can be used to «simulate» Null equality in join criteria, and the IS NULL and IS NOT NULL predicates can be used in the join criteria as well. The following predicate tests for equality of the values A and B and treats Nulls as being equal.

(A = B) OR (A IS NULL AND B IS NULL)

CASE expressions[edit]

SQL provides two flavours of conditional expressions. One is called «simple CASE» and operates like a switch statement. The other is called a «searched CASE» in the standard, and operates like an if…elseif.

The simple CASE expressions use implicit equality comparisons which operate under the same rules as the DML WHERE clause rules for Null. Thus, a simple CASE expression cannot check for the existence of Null directly. A check for Null in a simple CASE expression always results in Unknown, as in the following:

SELECT CASE i WHEN NULL THEN 'Is Null' -- This will never be returned WHEN 0 THEN 'Is Zero' -- This will be returned when i = 0 WHEN 1 THEN 'Is One' -- This will be returned when i = 1 END FROM t;

Because the expression i = NULL evaluates to Unknown no matter what value column i contains (even if it contains Null), the string 'Is Null' will never be returned.

On the other hand, a «searched» CASE expression can use predicates like IS NULL and IS NOT NULL in its conditions. The following example shows how to use a searched CASE expression to properly check for Null:

SELECT CASE WHEN i IS NULL THEN 'Null Result' -- This will be returned when i is NULL WHEN i = 0 THEN 'Zero' -- This will be returned when i = 0 WHEN i = 1 THEN 'One' -- This will be returned when i = 1 END FROM t;

In the searched CASE expression, the string 'Null Result' is returned for all rows in which i is Null.

Oracle’s dialect of SQL provides a built-in function DECODE which can be used instead of the simple CASE expressions and considers two nulls equal.

SELECT DECODE(i, NULL, 'Null Result', 0, 'Zero', 1, 'One') FROM t;

Finally, all these constructs return a NULL if no match is found; they have a default ELSE NULL clause.

IF statements in procedural extensions[edit]

SQL/PSM (SQL Persistent Stored Modules) defines procedural extensions for SQL, such as the IF statement. However, the major SQL vendors have historically included their own proprietary procedural extensions. Procedural extensions for looping and comparisons operate under Null comparison rules similar to those for DML statements and queries. The following code fragment, in ISO SQL standard format, demonstrates the use of Null 3VL in an IF statement.

IF i = NULL THEN SELECT 'Result is True' ELSEIF NOT(i = NULL) THEN SELECT 'Result is False' ELSE SELECT 'Result is Unknown';

The IF statement performs actions only for those comparisons that evaluate to True. For statements that evaluate to False or Unknown, the IF statement passes control to the ELSEIF clause, and finally to the ELSE clause. The result of the code above will always be the message 'Result is Unknown' since the comparisons with Null always evaluate to Unknown.

Analysis of SQL Null missing-value semantics[edit]

The groundbreaking work of T. Imieliński and W. Lipski Jr. (1984)[16] provided a framework in which to evaluate the intended semantics of various proposals to implement missing-value semantics, that is referred to as Imieliński-Lipski Algebras. This section roughly follows chapter 19 of the «Alice» textbook.[17] A similar presentation appears in the review of Ron van der Meyden, §10.4.[1]

In selections and projections: weak representation[edit]

Constructs representing missing information, such as Codd tables, are actually intended to represent a set of relations, one for each possible instantiation of their parameters; in the case of Codd tables, this means replacement of Nulls with some concrete value. For example,

Emp

| Name | Age |

|---|---|

| George | 43 |

| Harriet | NULL |

| Charles | 56 |

EmpH22

| Name | Age |

|---|---|

| George | 43 |

| Harriet | 22 |

| Charles | 56 |

EmpH37

| Name | Age |

|---|---|

| George | 43 |

| Harriet | 37 |

| Charles | 56 |

The Codd table Emp may represent the relation EmpH22 or EmpH37, as pictured.

A construct (such as a Codd table) is said to be a strong representation system (of missing information) if any answer to a query made on the construct can be particularized to obtain an answer for any corresponding query on the relations it represents, which are seen as models of the construct. More precisely, if q is a query formula in the relational algebra (of «pure» relations) and if q is its lifting to a construct intended to represent missing information, a strong representation has the property that for any query q and (table) construct T, q lifts all the answers to the construct, i.e.:

(The above has to hold for queries taking any number of tables as arguments, but the restriction to one table suffices for this discussion.) Clearly Codd tables do not have this strong property if selections and projections are considered as part of the query language. For example, all the answers to

SELECT * FROM Emp WHERE Age = 22;

should include the possibility that a relation like EmpH22 may exist. However, Codd tables cannot represent the disjunction «result with possibly 0 or 1 rows». A device, mostly of theoretical interest, called conditional table (or c-table) can however represent such an answer:

Result

| Name | Age | condition |

|---|---|---|

| Harriet | ω1 | ω1 = 22 |

where the condition column is interpreted as the row doesn’t exist if the condition is false. It turns out that because the formulas in the condition column of a c-table can be arbitrary propositional logic formulas, an algorithm for the problem whether a c-table represents some concrete relation has a co-NP-complete complexity, thus is of little practical worth.

A weaker notion of representation is therefore desirable. Imielinski and Lipski introduced the notion of weak representation, which essentially allows (lifted) queries over a construct to return a representation only for sure information, i.e. if it’s valid for all «possible world» instantiations (models) of the construct. Concretely, a construct is a weak representation system if

The right-hand side of the above equation is the sure information, i.e. information which can be certainly extracted from the database regardless of what values are used to replace Nulls in the database. In the example we considered above, it’s easy to see that the intersection of all possible models (i.e. the sure information) of the query selecting WHERE Age = 22 is actually empty because, for instance, the (unlifted) query returns no rows for the relation EmpH37. More generally, it was shown by Imielinski and Lipski that Codd tables are a weak representation system if the query language is restricted to projections, selections (and renaming of columns). However, as soon as we add either joins or unions to the query language, even this weak property is lost, as evidenced in the next section.

If joins or unions are considered: not even weak representation[edit]

Consider the following query over the same Codd table Emp from the previous section:

SELECT Name FROM Emp WHERE Age = 22 UNION SELECT Name FROM Emp WHERE Age <> 22;

Whatever concrete value one would choose for the NULL age of Harriet, the above query will return the full column of names of any model of Emp, but when the (lifted) query is run on Emp itself, Harriet will always be missing, i.e. we have:

| Query result on Emp: |

|

Query result on any model of Emp: |

|

Thus when unions are added to the query language, Codd tables are not even a weak representation system of missing information, meaning that queries over them don’t even report all sure information. It’s important to note here that semantics of UNION on Nulls, which are discussed in a later section, did not even come into play in this query. The «forgetful» nature of the two sub-queries was all that it took to guarantee that some sure information went unreported when the above query was run on the Codd table Emp.

For natural joins, the example needed to show that sure information may be unreported by some query is slightly more complicated. Consider the table

J

| F1 | F2 | F3 |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | NULL |

13 |

| 21 | NULL |

23 |

| 31 | 32 | 33 |

and the query

SELECT F1, F3 FROM (SELECT F1, F2 FROM J) AS F12 NATURAL JOIN (SELECT F2, F3 FROM J) AS F23;

| Query result on J: |

|

Query result on any model of J: |

|

The intuition for what happens above is that the Codd tables representing the projections in the subqueries lose track of the fact that the Nulls in the columns F12.F2 and F23.F2 are actually copies of the originals in the table J. This observation suggests that a relatively simple improvement of Codd tables (which works correctly for this example) would be to use Skolem constants (meaning Skolem functions which are also constant functions), say ω12 and ω22 instead of a single NULL symbol. Such an approach, called v-tables or Naive tables, is computationally less expensive that the c-tables discussed above. However, it is still not a complete solution for incomplete information in the sense that v-tables are only a weak representation for queries not using any negations in selection (and not using any set difference either). The first example considered in this section is using a negative selection clause, WHERE Age <> 22, so it is also an example where v-tables queries would not report sure information.

Check constraints and foreign keys[edit]

The primary place in which SQL three-valued logic intersects with SQL Data Definition Language (DDL) is in the form of check constraints. A check constraint placed on a column operates under a slightly different set of rules than those for the DML WHERE clause. While a DML WHERE clause must evaluate to True for a row, a check constraint must not evaluate to False. (From a logic perspective, the designated values are True and Unknown.) This means that a check constraint will succeed if the result of the check is either True or Unknown. The following example table with a check constraint will prohibit any integer values from being inserted into column i, but will allow Null to be inserted since the result of the check will always evaluate to Unknown for Nulls.[18]

CREATE TABLE t ( i INTEGER, CONSTRAINT ck_i CHECK ( i < 0 AND i = 0 AND i > 0 ) );

Because of the change in designated values relative to the WHERE clause, from a logic perspective the law of excluded middle is a tautology for CHECK constraints, meaning CHECK (p OR NOT p) always succeeds. Furthermore, assuming Nulls are to be interpreted as existing but unknown values, some pathological CHECKs like the one above allow insertion of Nulls that could never be replaced by any non-null value.

In order to constrain a column to reject Nulls, the NOT NULL constraint can be applied, as shown in the example below. The NOT NULL constraint is semantically equivalent to a check constraint with an IS NOT NULL predicate.

CREATE TABLE t ( i INTEGER NOT NULL );

By default check constraints against foreign keys succeed if any of the fields in such keys are Null. For example, the table

CREATE TABLE Books ( title VARCHAR(100), author_last VARCHAR(20), author_first VARCHAR(20), FOREIGN KEY (author_last, author_first) REFERENCES Authors(last_name, first_name));

would allow insertion of rows where author_last or author_first are NULL irrespective of how the table Authors is defined or what it contains. More precisely, a null in any of these fields would allow any value in the other one, even on that is not found in Authors table. For example, if Authors contained only ('Doe', 'John'), then ('Smith', NULL) would satisfy the foreign key constraint. SQL-92 added two extra options for narrowing down the matches in such cases. If MATCH PARTIAL is added after the REFERENCES declaration then any non-null must match the foreign key, e.g. ('Doe', NULL) would still match, but ('Smith', NULL) would not. Finally, if MATCH FULL is added then ('Smith', NULL) would not match the constraint either, but (NULL, NULL) would still match it.

Outer joins[edit]

Example SQL outer join query with Null placeholders in the result set. The Null markers are represented by the word NULL in place of data in the results. Results are from Microsoft SQL Server, as shown in SQL Server Management Studio.

SQL outer joins, including left outer joins, right outer joins, and full outer joins, automatically produce Nulls as placeholders for missing values in related tables. For left outer joins, for instance, Nulls are produced in place of rows missing from the table appearing on the right-hand side of the LEFT OUTER JOIN operator. The following simple example uses two tables to demonstrate Null placeholder production in a left outer join.

The first table (Employee) contains employee ID numbers and names, while the second table (PhoneNumber) contains related employee ID numbers and phone numbers, as shown below.

|

Employee

|

PhoneNumber

|

The following sample SQL query performs a left outer join on these two tables.

SELECT e.ID, e.LastName, e.FirstName, pn.Number FROM Employee e LEFT OUTER JOIN PhoneNumber pn ON e.ID = pn.ID;

The result set generated by this query demonstrates how SQL uses Null as a placeholder for values missing from the right-hand (PhoneNumber) table, as shown below.

Query result

| ID | LastName | FirstName | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Johnson | Joe | 555-2323 |

| 2 | Lewis | Larry | NULL

|

| 3 | Thompson | Thomas | 555-9876 |

| 4 | Patterson | Patricia | NULL

|

Aggregate functions[edit]

SQL defines aggregate functions to simplify server-side aggregate calculations on data. Except for the COUNT(*) function, all aggregate functions perform a Null-elimination step, so that Nulls are not included in the final result of the calculation.[19]

Note that the elimination of Null is not equivalent to replacing Null with zero. For example, in the following table, AVG(i) (the average of the values of i) will give a different result from that of AVG(j):

| i | j |

|---|---|

| 150 | 150 |

| 200 | 200 |

| 250 | 250 |

NULL

|

0 |

Here AVG(i) is 200 (the average of 150, 200, and 250), while AVG(j) is 150 (the average of 150, 200, 250, and 0). A well-known side effect of this is that in SQL AVG(z) is equivalent with not SUM(z)/COUNT(*) but SUM(z)/COUNT(z).[4]

The output of an aggregate function can also be Null. Here is an example:

SELECT COUNT(*), MIN(e.Wage), MAX(e.Wage) FROM Employee e WHERE e.LastName LIKE '%Jones%';

This query will always output exactly one row, counting of the number of employees whose last name contains «Jones», and giving the minimum and maximum wage found for those employees. However, what happens if none of the employees fit the given criteria? Calculating the minimum or maximum value of an empty set is impossible, so those results must be NULL, indicating there is no answer. This is not an Unknown value, it is a Null representing the absence of a value. The result would be:

| COUNT(*) | MIN(e.Wage) | MAX(e.Wage) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | NULL

|

NULL

|

When two nulls are equal: grouping, sorting, and some set operations[edit]

Because SQL:2003 defines all Null markers as being unequal to one another, a special definition was required in order to group Nulls together when performing certain operations. SQL defines «any two values that are equal to one another, or any two Nulls», as «not distinct».[20] This definition of not distinct allows SQL to group and sort Nulls when the GROUP BY clause (and other keywords that perform grouping) are used.

Other SQL operations, clauses, and keywords use «not distinct» in their treatment of Nulls. These include the following:

PARTITION BYclause of ranking and windowing functions likeROW_NUMBERUNION,INTERSECT, andEXCEPToperator, which treat NULLs as the same for row comparison/elimination purposesDISTINCTkeyword used inSELECTqueries

The principle that Nulls aren’t equal to each other (but rather that the result is Unknown) is effectively violated in the SQL specification for the UNION operator, which does identify nulls with each other.[1] Consequently, some set operations in SQL, like union or difference, may produce results not representing sure information, unlike operations involving explicit comparisons with NULL (e.g. those in a WHERE clause discussed above). In Codd’s 1979 proposal (which was basically adopted by SQL92) this semantic inconsistency is rationalized by arguing that removal of duplicates in set operations happens «at a lower level of detail than equality testing in the evaluation of retrieval operations.»[10]

The SQL standard does not explicitly define a default sort order for Nulls. Instead, on conforming systems, Nulls can be sorted before or after all data values by using the NULLS FIRST or NULLS LAST clauses of the ORDER BY list, respectively. Not all DBMS vendors implement this functionality, however. Vendors who do not implement this functionality may specify different treatments for Null sorting in the DBMS.[18]

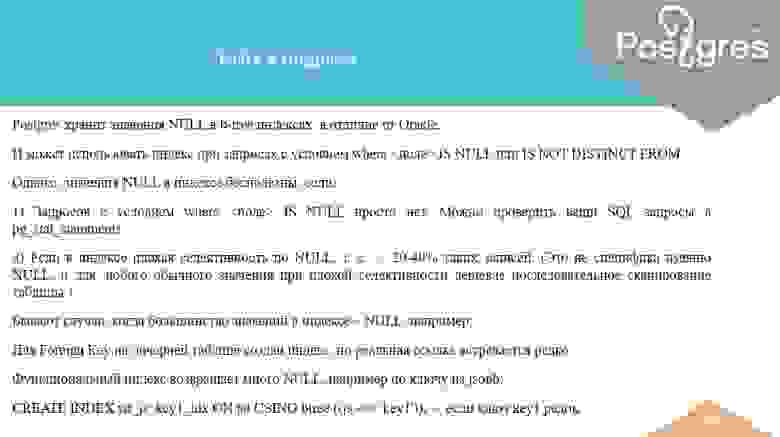

Effect on index operation[edit]

Some SQL products do not index keys containing NULLs. For instance, PostgreSQL versions prior to 8.3 did not, with the documentation for a B-tree index stating that[21]

B-trees can handle equality and range queries on data that can be sorted into some ordering. In particular, the PostgreSQL query planner will consider using a B-tree index whenever an indexed column is involved in a comparison using one of these operators: < ≤ = ≥ >

Constructs equivalent to combinations of these operators, such as BETWEEN and IN, can also be implemented with a B-tree index search. (But note that IS NULL is not equivalent to = and is not indexable.)

In cases where the index enforces uniqueness, NULLs are excluded from the index and uniqueness is not enforced between NULLs. Again, quoting from the PostgreSQL documentation:[22]

When an index is declared unique, multiple table rows with equal indexed values will not be allowed. Nulls are not considered equal. A multicolumn unique index will only reject cases where all of the indexed columns are equal in two rows.

This is consistent with the SQL:2003-defined behavior of scalar Null comparisons.

Another method of indexing Nulls involves handling them as not distinct in accordance with the SQL:2003-defined behavior. For example, Microsoft SQL Server documentation states the following:[23]

For indexing purposes, NULLs compare as equal. Therefore, a unique index, or UNIQUE constraint, cannot be created if the keys are NULL in more than one row. Select columns that are defined as NOT NULL when columns for a unique index or unique constraint are chosen.

Both of these indexing strategies are consistent with the SQL:2003-defined behavior of Nulls. Because indexing methodologies are not explicitly defined by the SQL:2003 standard, indexing strategies for Nulls are left entirely to the vendors to design and implement.

Null-handling functions[edit]

SQL defines two functions to explicitly handle Nulls: NULLIF and COALESCE. Both functions are abbreviations for searched CASE expressions.[24]

NULLIF[edit]

The NULLIF function accepts two parameters. If the first parameter is equal to the second parameter, NULLIF returns Null. Otherwise, the value of the first parameter is returned.

Thus, NULLIF is an abbreviation for the following CASE expression:

CASE WHEN value1 = value2 THEN NULL ELSE value1 END

COALESCE[edit]

The COALESCE function accepts a list of parameters, returning the first non-Null value from the list:

COALESCE(value1, value2, value3, ...)

COALESCE is defined as shorthand for the following SQL CASE expression:

CASE WHEN value1 IS NOT NULL THEN value1 WHEN value2 IS NOT NULL THEN value2 WHEN value3 IS NOT NULL THEN value3 ... END

Some SQL DBMSs implement vendor-specific functions similar to COALESCE. Some systems (e.g. Transact-SQL) implement an ISNULL function, or other similar functions that are functionally similar to COALESCE. (See Is functions for more on the IS functions in Transact-SQL.)

NVL[edit]

«NVL» redirects here. For the gene, see NVL (gene).

The Oracle NVL function accepts two parameters. It returns the first non-NULL parameter or NULL if all parameters are NULL.

A COALESCE expression can be converted into an equivalent NVL expression thus:

COALESCE ( val1, ... , val{n} )

turns into:

NVL( val1 , NVL( val2 , NVL( val3 , … , NVL ( val{n-1} , val{n} ) … )))

A use case of this function is to replace in an expression a NULL by a value like in NVL(SALARY, 0) which says, ‘if SALARY is NULL, replace it with the value 0′.

There is, however, one notable exception. In most implementations, COALESCE evaluates its parameters until it reaches the first non-NULL one, while NVL evaluates all of its parameters. This is important for several reasons. A parameter after the first non-NULL parameter could be a function, which could either be computationally expensive, invalid, or could create unexpected side effects.

Data typing of Null and Unknown[edit]

The NULL literal is untyped in SQL, meaning that it is not designated as an integer, character, or any other specific data type.[25] Because of this, it is sometimes mandatory (or desirable) to explicitly convert Nulls to a specific data type. For instance, if overloaded functions are supported by the RDBMS, SQL might not be able to automatically resolve to the correct function without knowing the data types of all parameters, including those for which Null is passed.

Conversion from the NULL literal to a Null of a specific type is possible using the CAST introduced in SQL-92. For example:

represents an absent value of type INTEGER.

The actual typing of Unknown (distinct or not from NULL itself) varies between SQL implementations. For example, the following

SELECT 'ok' WHERE (NULL <> 1) IS NULL;

parses and executes successfully in some environments (e.g. SQLite or PostgreSQL) which unify a NULL boolean with Unknown but fails to parse in others (e.g. in SQL Server Compact). MySQL behaves similarly to PostgreSQL in this regard (with the minor exception that MySQL regards TRUE and FALSE as no different from the ordinary integers 1 and 0). PostgreSQL additionally implements a IS UNKNOWN predicate, which can be used to test whether a three-value logical outcome is Unknown, although this is merely syntactic sugar.

BOOLEAN data type[edit]

The ISO SQL:1999 standard introduced the BOOLEAN data type to SQL, however it’s still just an optional, non-core feature, coded T031.[26]

When restricted by a NOT NULL constraint, the SQL BOOLEAN works like the Boolean type from other languages. Unrestricted however, the BOOLEAN datatype, despite its name, can hold the truth values TRUE, FALSE, and UNKNOWN, all of which are defined as boolean literals according to the standard. The standard also asserts that NULL and UNKNOWN «may be used

interchangeably to mean exactly the same thing».[27][28]

The Boolean type has been subject of criticism, particularly because of the mandated behavior of the UNKNOWN literal, which is never equal to itself because of the identification with NULL.[29]

As discussed above, in the PostgreSQL implementation of SQL, Null is used to represent all UNKNOWN results, including the UNKNOWN BOOLEAN. PostgreSQL does not implement the UNKNOWN literal (although it does implement the IS UNKNOWN operator, which is an orthogonal feature.) Most other major vendors do not support the Boolean type (as defined in T031) as of 2012.[30] The procedural part of Oracle’s PL/SQL supports BOOLEAN however variables; these can also be assigned NULL and the value is considered the same as UNKNOWN.[31]

Controversy[edit]

Common mistakes[edit]

Misunderstanding of how Null works is the cause of a great number of errors in SQL code, both in ISO standard SQL statements and in the specific SQL dialects supported by real-world database management systems. These mistakes are usually the result of confusion between Null and either 0 (zero) or an empty string (a string value with a length of zero, represented in SQL as ''). Null is defined by the SQL standard as different from both an empty string and the numerical value 0, however. While Null indicates the absence of any value, the empty string and numerical zero both represent actual values.

A classic error is the attempt to use the equals operator = in combination with the keyword NULL to find rows with Nulls. According to the SQL standard this is an invalid syntax and shall lead to an error message or an exception. But most implementations accept the syntax and evaluate such expressions to UNKNOWN. The consequence is that no rows are found – regardless of whether rows with Nulls exist or not. The proposed way to retrieve rows with Nulls is the use of the predicate IS NULL instead of = NULL.

SELECT * FROM sometable WHERE num = NULL; -- Should be "WHERE num IS NULL"

In a related, but more subtle example, a WHERE clause or conditional statement might compare a column’s value with a constant. It is often incorrectly assumed that a missing value would be «less than» or «not equal to» a constant if that field contains Null, but, in fact, such expressions return Unknown. An example is below:

SELECT * FROM sometable WHERE num <> 1; -- Rows where num is NULL will not be returned, -- contrary to many users' expectations.

These confusions arise because the Law of Identity is restricted in SQL’s logic. When dealing with equality comparisons using the NULL literal or the UNKNOWN truth-value, SQL will always return UNKNOWN as the result of the expression. This is a partial equivalence relation and makes SQL an example of a Non-Reflexive logic.[32]

Similarly, Nulls are often confused with empty strings. Consider the LENGTH function, which returns the number of characters in a string. When a Null is passed into this function, the function returns Null. This can lead to unexpected results, if users are not well versed in 3-value logic. An example is below:

SELECT * FROM sometable WHERE LENGTH(string) < 20; -- Rows where string is NULL will not be returned.

This is complicated by the fact that in some database interface programs (or even database implementations like Oracle’s), NULL is reported as an empty string, and empty strings may be incorrectly stored as NULL.

Criticisms[edit]

The ISO SQL implementation of Null is the subject of criticism, debate and calls for change. In The Relational Model for Database Management: Version 2, Codd suggested that the SQL implementation of Null was flawed and should be replaced by two distinct Null-type markers. The markers he proposed were to stand for «Missing but Applicable» and «Missing but Inapplicable», known as A-values and I-values, respectively. Codd’s recommendation, if accepted, would have required the implementation of a four-valued logic in SQL.[5] Others have suggested adding additional Null-type markers to Codd’s recommendation to indicate even more reasons that a data value might be «Missing», increasing the complexity of SQL’s logic system. At various times, proposals have also been put forth to implement multiple user-defined Null markers in SQL. Because of the complexity of the Null-handling and logic systems required to support multiple Null markers, none of these proposals have gained widespread acceptance.

Chris Date and Hugh Darwen, authors of The Third Manifesto, have suggested that the SQL Null implementation is inherently flawed and should be eliminated altogether,[33] pointing to inconsistencies and flaws in the implementation of SQL Null-handling (particularly in aggregate functions) as proof that the entire concept of Null is flawed and should be removed from the relational model.[34] Others, like author Fabian Pascal, have stated a belief that «how the function calculation should treat missing values is not governed by the relational model.»[citation needed]

Closed-world assumption[edit]

Another point of conflict concerning Nulls is that they violate the closed-world assumption model of relational databases by introducing an open-world assumption into it.[35] The closed world assumption, as it pertains to databases, states that «Everything stated by the database, either explicitly or implicitly, is true; everything else is false.»[36] This view assumes that the knowledge of the world stored within a database is complete. Nulls, however, operate under the open world assumption, in which some items stored in the database are considered unknown, making the database’s stored knowledge of the world incomplete.

See also[edit]

- SQL

- NULLs in: Wikibook SQL

- Ternary logic

- Data manipulation language

- Codd’s 12 rules

- Check constraint

- Relational Model/Tasmania

- Relational database management system

- Join (SQL)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Ron van der Meyden, «Logical approaches to incomplete information: a survey» in Chomicki, Jan; Saake, Gunter (Eds.) Logics for Databases and Information Systems, Kluwer Academic Publishers ISBN 978-0-7923-8129-7, p. 344; PS preprint (note: page numbering differs in preprint from the published version)

- ^ Codd, E.F. (October 14, 1985). «Is Your Database Really Relational?». Computerworld.

- ^ Codd, E.F. (October 21, 1985). «Does Your DBMS Run By The Rules?». Computerworld.

- ^ a b Don Chamberlin (1998). A Complete Guide to DB2 Universal Database. Morgan Kaufmann. pp. 28–32. ISBN 978-1-55860-482-7.

- ^ a b Codd, E.F. (1990). The Relational Model for Database Management (Version 2 ed.). Addison Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-201-14192-4.

- ^ a b ISO/IEC (2003). ISO/IEC 9075-2:2003, «SQL/Foundation». ISO/IEC. Section 6.2.6: numeric value expressions..

- ^

ISO/IEC (2003). ISO/IEC 9075-2:2003, «SQL/Foundation». ISO/IEC. Section 6.2.8: string value expression. - ^

ISO/IEC (2003). ISO/IEC 9075-1:2003, «SQL/Framework». ISO/IEC. Section 4.4.2: The null value. - ^ a b Coles, Michael (June 27, 2005). «Four Rules for Nulls». SQL Server Central. Red Gate Software.

- ^ a b Hans-Joachim, K. (2003). «Null Values in Relational Databases and Sure Information Answers». Semantics in Databases. Second International Workshop Dagstuhl Castle, Germany, January 7–12, 2001. Revised Papers. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2582. pp. 119–138. doi:10.1007/3-540-36596-6_7. ISBN 978-3-540-00957-3.

- ^

ISO/IEC (2003). ISO/IEC 9075-2:2003, «SQL/Foundation». ISO/IEC. Section 8.7: null predicate. - ^ C.J. Date (2004), An introduction to database systems, 8th ed., Pearson Education, p. 594

- ^ Jim Melton; Jim Melton Alan R. Simon (1993). Understanding The New SQL: A Complete Guide. Morgan Kaufmann. pp. 145–147. ISBN 978-1-55860-245-8.

- ^ C. J. Date, Relational database writings, 1991-1994, Addison-Wesley, 1995, p. 371

- ^ C.J. Date (2004), An introduction to database systems, 8th ed., Pearson Education, p. 584

- ^ Imieliński, T.; Lipski Jr., W. (1984). «Incomplete information in relational databases». Journal of the ACM. 31 (4): 761–791. doi:10.1145/1634.1886. S2CID 288040.

- ^ Abiteboul, Serge; Hull, Richard B.; Vianu, Victor (1995). Foundations of Databases. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-53771-0.

- ^ a b Coles, Michael (February 26, 2007). «Null Versus Null?». SQL Server Central. Red Gate Software.

- ^

ISO/IEC (2003). ISO/IEC 9075-2:2003, «SQL/Foundation». ISO/IEC. Section 4.15.4: Aggregate functions. - ^ ISO/IEC (2003). ISO/IEC 9075-2:2003, «SQL/Foundation». ISO/IEC. Section 3.1.6.8: Definitions: distinct.

- ^ «PostgreSQL 8.0.14 Documentation: Index Types». PostgreSQL. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ «PostgreSQL 8.0.14 Documentation: Unique Indexes». PostgreSQL. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ^ «Creating Unique Indexes». PostfreSQL. September 2007. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ^

ISO/IEC (2003). ISO/IEC 9075-2:2003, «SQL/Foundation». ISO/IEC. Section 6.11: case expression. - ^ Jim Melton; Alan R. Simon (2002). SQL:1999: Understanding Relational Language Components. Morgan Kaufmann. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-55860-456-8.

- ^ «ISO/IEC 9075-1:1999 SQL Standard». ISO. 1999.

- ^ C. Date (2011). SQL and Relational Theory: How to Write Accurate SQL Code. O’Reilly Media, Inc. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-4493-1640-2.

- ^ ISO/IEC 9075-2:2011 §4.5

- ^ Martyn Prigmore (2007). Introduction to Databases With Web Applications. Pearson Education Canada. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-321-26359-9.

- ^ Troels Arvin, Survey of BOOLEAN data type implementation

- ^ Steven Feuerstein; Bill Pribyl (2009). Oracle PL/SQL Programming. O’Reilly Media, Inc. pp. 74, 91. ISBN 978-0-596-51446-4.

- ^ Arenhart, Krause (2012), «Classical Logic or Non-Reflexive Logic? A case of Semantic Underdetermination», Revista Portuguesa de Filosofia, 68 (1/2): 73–86, doi:10.17990/RPF/2012_68_1_0073, JSTOR 41955624.

- ^

Darwen, Hugh; Chris Date. «The Third Manifesto». Retrieved May 29, 2007. - ^

Darwen, Hugh. «The Askew Wall» (PDF). Retrieved May 29, 2007. - ^ Date, Chris (May 2005). Database in Depth: Relational Theory for Practitioners. O’Reilly Media, Inc. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-596-10012-4.

- ^ Date, Chris. «Abstract: The Closed World Assumption». Data Management Association, San Francisco Bay Area Chapter. Archived from the original on 2007-05-19. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

Further reading[edit]

- E. F. Codd. Understanding relations (installment #7). FDT Bulletin of ACM-SIGMOD, 7(3-4):23–28, 1975.

- Codd, E. F. (1979). «Extending the database relational model to capture more meaning». ACM Transactions on Database Systems. 4 (4): 397–434. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.508.5701. doi:10.1145/320107.320109. S2CID 17517212. Especially §2.3.

- Date, C.J. (2000). The Database Relational Model: A Retrospective Review and Analysis: A Historical Account and Assessment of E. F. Codd’s Contribution to the Field of Database Technology. Addison Wesley Longman. ISBN 978-0-201-61294-3.

- Klein, Hans-Joachim (1994). «How to modify SQL queries in order to guarantee sure answers». ACM SIGMOD Record. 23 (3): 14–20. doi:10.1145/187436.187445. S2CID 17354724.

- Claude Rubinson, Nulls, Three-Valued Logic, and Ambiguity in SQL: Critiquing Date’s Critique, SIGMOD Record, December 2007 (Vol. 36, No. 4)

- John Grant, Null Values in SQL. SIGMOD Record, September 2008 (Vol. 37, No. 3)

- Waraporn, Narongrit, and Kriengkrai Porkaew. «Null semantics for subqueries and atomic predicates». IAENG International Journal of Computer Science 35.3 (2008): 305-313.

- Bernhard Thalheim, Klaus-Dieter Schewe (2011). «NULL ‘Value’ Algebras and Logics». Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications. 225 (Information Modelling and Knowledge Bases XXII). doi:10.3233/978-1-60750-690-4-354.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Enrico Franconi and Sergio Tessaris, On the Logic of SQL Nulls, Proceedings of the 6th Alberto Mendelzon International Workshop on Foundations of Data Management, Ouro Preto, Brazil, June 27–30, 2012. pp. 114–128

External links[edit]

- Oracle NULLs Archived 2013-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- The Third Manifesto

- Implications of NULLs in sequencing of data

- Java bug report about jdbc not distinguishing null and empty string, which Sun closed as «not a bug»

In SQL, null or NULL is a special marker used to indicate that a data value does not exist in the database. Introduced by the creator of the relational database model, E. F. Codd, SQL null serves to fulfil the requirement that all true relational database management systems (RDBMS) support a representation of «missing information and inapplicable information». Codd also introduced the use of the lowercase Greek omega (ω) symbol to represent null in database theory. In SQL, NULL is a reserved word used to identify this marker.

A null should not be confused with a value of 0. A null value indicates a lack of a value, which is not the same thing as a value of zero. For example, consider the question «How many books does Adam own?» The answer may be «zero» (we know that he owns none) or «null» (we do not know how many he owns). In a database table, the column reporting this answer would start out with no value (marked by Null), and it would not be updated with the value «zero» until we have ascertained that Adam owns no books.

SQL null is a marker, not a value. This usage is quite different from most programming languages, where null value of a reference means it is not pointing to any object.

History[edit]

E. F. Codd mentioned nulls as a method of representing missing data in the relational model in a 1975 paper in the FDT Bulletin of ACM-SIGMOD. Codd’s paper that is most commonly cited in relation with the semantics of Null (as adopted in SQL) is his 1979 paper in the ACM Transactions on Database Systems, in which he also introduced his Relational Model/Tasmania, although much of the other proposals from the latter paper have remained obscure. Section 2.3 of his 1979 paper details the semantics of Null propagation in arithmetic operations as well as comparisons employing a ternary (three-valued) logic when comparing to nulls; it also details the treatment of Nulls on other set operations (the latter issue still controversial today). In database theory circles, the original proposal of Codd (1975, 1979) is now referred to as «Codd tables».[1] Codd later reinforced his requirement that all RDBMSs support Null to indicate missing data in a 1985 two-part article published in Computerworld magazine.[2][3]

The 1986 SQL standard basically adopted Codd’s proposal after an implementation prototype in IBM System R. Although Don Chamberlin recognized nulls (alongside duplicate rows) as one of the most controversial features of SQL, he defended the design of Nulls in SQL invoking the pragmatic arguments that it was the least expensive form of system support for missing information, saving the programmer from many duplicative application-level checks (see semipredicate problem) while at the same time providing the database designer with the option not to use Nulls if they so desire; for example, in order to avoid well known anomalies (discussed in the semantics section of this article). Chamberlin also argued that besides providing some missing-value functionality, practical experience with Nulls also led to other language features which rely on Nulls, like certain grouping constructs and outer joins. Finally, he argued that in practice Nulls also end up being used as a quick way to patch an existing schema when it needs to evolve beyond its original intent, coding not for missing but rather for inapplicable information; for example, a database that quickly needs to support electric cars while having a miles-per-gallon column.[4]

Codd indicated in his 1990 book The Relational Model for Database Management, Version 2 that the single Null mandated by the SQL standard was inadequate, and should be replaced by two separate Null-type markers to indicate the reason why data is missing. In Codd’s book, these two Null-type markers are referred to as ‘A-Values’ and ‘I-Values’, representing ‘Missing But Applicable’ and ‘Missing But Inapplicable’, respectively.[5] Codd’s recommendation would have required SQL’s logic system be expanded to accommodate a four-valued logic system. Because of this additional complexity, the idea of multiple Nulls with different definitions has not gained widespread acceptance in the database practitioners’ domain. It remains an active field of research though, with numerous papers still being published.

Challenges[edit]

Null has been the focus of controversy and a source of debate because of its associated three-valued logic (3VL), special requirements for its use in SQL joins, and the special handling required by aggregate functions and SQL grouping operators. Computer science professor Ron van der Meyden summarized the various issues as: «The inconsistencies in the SQL standard mean that it is not possible to ascribe any intuitive logical semantics to the treatment of nulls in SQL.»[1] Although various proposals have been made for resolving these issues, the complexity of the alternatives has prevented their widespread adoption.

Null propagation[edit]

Arithmetic operations[edit]

Because Null is not a data value, but a marker for an absent value, using mathematical operators on Null gives an unknown result, which is represented by Null.[6] In the following example, multiplying 10 by Null results in Null:

10 * NULL -- Result is NULL

This can lead to unanticipated results. For instance, when an attempt is made to divide Null by zero, platforms may return Null instead of throwing an expected «data exception – division by zero».[6] Though this behavior is not defined by the ISO SQL standard many DBMS vendors treat this operation similarly. For instance, the Oracle, PostgreSQL, MySQL Server, and Microsoft SQL Server platforms all return a Null result for the following:

String concatenation[edit]

String concatenation operations, which are common in SQL, also result in Null when one of the operands is Null.[7] The following example demonstrates the Null result returned by using Null with the SQL || string concatenation operator.

'Fish ' || NULL || 'Chips' -- Result is NULL

This is not true for all database implementations. In an Oracle RDBMS for example NULL and the empty string are considered the same thing and therefore ‘Fish ‘ || NULL || ‘Chips’ results in ‘Fish Chips’.

Comparisons with NULL and the three-valued logic (3VL)[edit]

Since Null is not a member of any data domain, it is not considered a «value», but rather a marker (or placeholder) indicating the undefined value. Because of this, comparisons with Null can never result in either True or False, but always in a third logical result, Unknown.[8] The logical result of the expression below, which compares the value 10 to Null, is Unknown:

SELECT 10 = NULL -- Results in Unknown

However, certain operations on Null can return values if the absent value is not relevant to the outcome of the operation. Consider the following example:

SELECT NULL OR TRUE -- Results in True

In this case, the fact that the value on the left of OR is unknowable is irrelevant, because the outcome of the OR operation would be True regardless of the value on the left.

SQL implements three logical results, so SQL implementations must provide for a specialized three-valued logic (3VL). The rules governing SQL three-valued logic are shown in the tables below (p and q represent logical states)»[9] The truth tables SQL uses for AND, OR, and NOT correspond to a common fragment of the Kleene and Łukasiewicz three-valued logic (which differ in their definition of implication, however SQL defines no such operation).[10]

| p | q | p OR q | p AND q | p = q |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | True | True | True | True |

| True | False | True | False | False |

| True | Unknown | True | Unknown | Unknown |

| False | True | True | False | False |

| False | False | False | False | True |

| False | Unknown | Unknown | False | Unknown |

| Unknown | True | True | Unknown | Unknown |

| Unknown | False | Unknown | False | Unknown |

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| p | NOT p |

|---|---|

| True | False |

| False | True |

| Unknown | Unknown |

Effect of Unknown in WHERE clauses[edit]

SQL three-valued logic is encountered in Data Manipulation Language (DML) in comparison predicates of DML statements and queries. The WHERE clause causes the DML statement to act on only those rows for which the predicate evaluates to True. Rows for which the predicate evaluates to either False or Unknown are not acted on by INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE DML statements, and are discarded by SELECT queries. Interpreting Unknown and False as the same logical result is a common error encountered while dealing with Nulls.[9] The following simple example demonstrates this fallacy:

SELECT * FROM t WHERE i = NULL;

The example query above logically always returns zero rows because the comparison of the i column with Null always returns Unknown, even for those rows where i is Null. The Unknown result causes the SELECT statement to summarily discard each and every row. (However, in practice, some SQL tools will retrieve rows using a comparison with Null.)

Null-specific and 3VL-specific comparison predicates[edit]

Basic SQL comparison operators always return Unknown when comparing anything with Null, so the SQL standard provides for two special Null-specific comparison predicates. The IS NULL and IS NOT NULL predicates (which use a postfix syntax) test whether data is, or is not, Null.[11]

The SQL standard contains the optional feature F571 «Truth value tests» that introduces three additional logical unary operators (six in fact, if we count their negation, which is part of their syntax), also using postfix notation. They have the following truth tables:[12]

| p | p IS TRUE | p IS NOT TRUE | p IS FALSE | p IS NOT FALSE | p IS UNKNOWN | p IS NOT UNKNOWN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | True | False | False | True | False | True |

| False | False | True | True | False | False | True |

| Unknown | False | True | False | True | True | False |

The F571 feature is orthogonal to the presence of the boolean datatype in SQL (discussed later in this article) and, despite syntactic similarities, F571 does not introduce boolean or three-valued literals in the language. The F571 feature was actually present in SQL92,[13] well before the boolean datatype was introduced to the standard in 1999. The F571 feature is implemented by few systems however; PostgreSQL is one of those implementing it.

The addition of IS UNKNOWN to the other operators of SQL’s three-valued logic makes the SQL three-valued logic functionally complete,[14] meaning its logical operators can express (in combination) any conceivable three-valued logical function.

On systems which don’t support the F571 feature, it is possible to emulate IS UNKNOWN p by going over every argument that could make the expression p Unknown and test those arguments with IS NULL or other NULL-specific functions, although this may be more cumbersome.

Law of the excluded fourth (in WHERE clauses)[edit]

In SQL’s three-valued logic the law of the excluded middle, p OR NOT p, no longer evaluates to true for all p. More precisely, in SQL’s three-valued logic p OR NOT p is unknown precisely when p is unknown and true otherwise. Because direct comparisons with Null result in the unknown logical value, the following query

SELECT * FROM stuff WHERE ( x = 10 ) OR NOT ( x = 10 );

is not equivalent in SQL with

if the column x contains any Nulls; in that case the second query would return some rows the first one does not return, namely all those in which x is Null. In classical two-valued logic, the law of the excluded middle would allow the simplification of the WHERE clause predicate, in fact its elimination. Attempting to apply the law of the excluded middle to SQL’s 3VL is effectively a false dichotomy. The second query is actually equivalent with:

SELECT * FROM stuff; -- is (because of 3VL) equivalent to: SELECT * FROM stuff WHERE ( x = 10 ) OR NOT ( x = 10 ) OR x IS NULL;

Thus, to correctly simplify the first statement in SQL requires that we return all rows in which x is not null.

SELECT * FROM stuff WHERE x IS NOT NULL;

In view of the above, observe that for SQL’s WHERE clause a tautology similar to the law of excluded middle can be written. Assuming the IS UNKNOWN operator is present, p OR (NOT p) OR (p IS UNKNOWN) is true for every predicate p. Among logicians, this is called law of excluded fourth.

There are some SQL expressions in which it is less obvious where the false dilemma occurs, for example:

SELECT 'ok' WHERE 1 NOT IN (SELECT CAST (NULL AS INTEGER)) UNION SELECT 'ok' WHERE 1 IN (SELECT CAST (NULL AS INTEGER));

produces no rows because IN translates to an iterated version of equality over the argument set and 1<>NULL is Unknown, just as a 1=NULL is Unknown. (The CAST in this example is needed only in some SQL implementations like PostgreSQL, which would reject it with a type checking error otherwise. In many systems plain SELECT NULL works in the subquery.) The missing case above is of course:

SELECT 'ok' WHERE (1 IN (SELECT CAST (NULL AS INTEGER))) IS UNKNOWN;

Effect of Null and Unknown in other constructs[edit]

Joins[edit]

Joins evaluate using the same comparison rules as for WHERE clauses. Therefore, care must be taken when using nullable columns in SQL join criteria. In particular a table containing any nulls is not equal with a natural self-join of itself, meaning that whereas

The SQL COALESCE function or CASE expressions can be used to «simulate» Null equality in join criteria, and the IS NULL and IS NOT NULL predicates can be used in the join criteria as well. The following predicate tests for equality of the values A and B and treats Nulls as being equal.

(A = B) OR (A IS NULL AND B IS NULL)

CASE expressions[edit]

SQL provides two flavours of conditional expressions. One is called «simple CASE» and operates like a switch statement. The other is called a «searched CASE» in the standard, and operates like an if…elseif.

The simple CASE expressions use implicit equality comparisons which operate under the same rules as the DML WHERE clause rules for Null. Thus, a simple CASE expression cannot check for the existence of Null directly. A check for Null in a simple CASE expression always results in Unknown, as in the following:

SELECT CASE i WHEN NULL THEN 'Is Null' -- This will never be returned WHEN 0 THEN 'Is Zero' -- This will be returned when i = 0 WHEN 1 THEN 'Is One' -- This will be returned when i = 1 END FROM t;

Because the expression i = NULL evaluates to Unknown no matter what value column i contains (even if it contains Null), the string 'Is Null' will never be returned.

On the other hand, a «searched» CASE expression can use predicates like IS NULL and IS NOT NULL in its conditions. The following example shows how to use a searched CASE expression to properly check for Null:

SELECT CASE WHEN i IS NULL THEN 'Null Result' -- This will be returned when i is NULL WHEN i = 0 THEN 'Zero' -- This will be returned when i = 0 WHEN i = 1 THEN 'One' -- This will be returned when i = 1 END FROM t;

In the searched CASE expression, the string 'Null Result' is returned for all rows in which i is Null.

Oracle’s dialect of SQL provides a built-in function DECODE which can be used instead of the simple CASE expressions and considers two nulls equal.

SELECT DECODE(i, NULL, 'Null Result', 0, 'Zero', 1, 'One') FROM t;

Finally, all these constructs return a NULL if no match is found; they have a default ELSE NULL clause.

IF statements in procedural extensions[edit]

SQL/PSM (SQL Persistent Stored Modules) defines procedural extensions for SQL, such as the IF statement. However, the major SQL vendors have historically included their own proprietary procedural extensions. Procedural extensions for looping and comparisons operate under Null comparison rules similar to those for DML statements and queries. The following code fragment, in ISO SQL standard format, demonstrates the use of Null 3VL in an IF statement.

IF i = NULL THEN SELECT 'Result is True' ELSEIF NOT(i = NULL) THEN SELECT 'Result is False' ELSE SELECT 'Result is Unknown';

The IF statement performs actions only for those comparisons that evaluate to True. For statements that evaluate to False or Unknown, the IF statement passes control to the ELSEIF clause, and finally to the ELSE clause. The result of the code above will always be the message 'Result is Unknown' since the comparisons with Null always evaluate to Unknown.

Analysis of SQL Null missing-value semantics[edit]

The groundbreaking work of T. Imieliński and W. Lipski Jr. (1984)[16] provided a framework in which to evaluate the intended semantics of various proposals to implement missing-value semantics, that is referred to as Imieliński-Lipski Algebras. This section roughly follows chapter 19 of the «Alice» textbook.[17] A similar presentation appears in the review of Ron van der Meyden, §10.4.[1]

In selections and projections: weak representation[edit]

Constructs representing missing information, such as Codd tables, are actually intended to represent a set of relations, one for each possible instantiation of their parameters; in the case of Codd tables, this means replacement of Nulls with some concrete value. For example,

Emp

| Name | Age |

|---|---|

| George | 43 |

| Harriet | NULL |

| Charles | 56 |

EmpH22

| Name | Age |

|---|---|

| George | 43 |

| Harriet | 22 |

| Charles | 56 |

EmpH37

| Name | Age |

|---|---|

| George | 43 |

| Harriet | 37 |

| Charles | 56 |

The Codd table Emp may represent the relation EmpH22 or EmpH37, as pictured.

A construct (such as a Codd table) is said to be a strong representation system (of missing information) if any answer to a query made on the construct can be particularized to obtain an answer for any corresponding query on the relations it represents, which are seen as models of the construct. More precisely, if q is a query formula in the relational algebra (of «pure» relations) and if q is its lifting to a construct intended to represent missing information, a strong representation has the property that for any query q and (table) construct T, q lifts all the answers to the construct, i.e.:

(The above has to hold for queries taking any number of tables as arguments, but the restriction to one table suffices for this discussion.) Clearly Codd tables do not have this strong property if selections and projections are considered as part of the query language. For example, all the answers to

SELECT * FROM Emp WHERE Age = 22;

should include the possibility that a relation like EmpH22 may exist. However, Codd tables cannot represent the disjunction «result with possibly 0 or 1 rows». A device, mostly of theoretical interest, called conditional table (or c-table) can however represent such an answer:

Result

| Name | Age | condition |

|---|---|---|

| Harriet | ω1 | ω1 = 22 |

where the condition column is interpreted as the row doesn’t exist if the condition is false. It turns out that because the formulas in the condition column of a c-table can be arbitrary propositional logic formulas, an algorithm for the problem whether a c-table represents some concrete relation has a co-NP-complete complexity, thus is of little practical worth.

A weaker notion of representation is therefore desirable. Imielinski and Lipski introduced the notion of weak representation, which essentially allows (lifted) queries over a construct to return a representation only for sure information, i.e. if it’s valid for all «possible world» instantiations (models) of the construct. Concretely, a construct is a weak representation system if

The right-hand side of the above equation is the sure information, i.e. information which can be certainly extracted from the database regardless of what values are used to replace Nulls in the database. In the example we considered above, it’s easy to see that the intersection of all possible models (i.e. the sure information) of the query selecting WHERE Age = 22 is actually empty because, for instance, the (unlifted) query returns no rows for the relation EmpH37. More generally, it was shown by Imielinski and Lipski that Codd tables are a weak representation system if the query language is restricted to projections, selections (and renaming of columns). However, as soon as we add either joins or unions to the query language, even this weak property is lost, as evidenced in the next section.

If joins or unions are considered: not even weak representation[edit]

Consider the following query over the same Codd table Emp from the previous section:

SELECT Name FROM Emp WHERE Age = 22 UNION SELECT Name FROM Emp WHERE Age <> 22;

Whatever concrete value one would choose for the NULL age of Harriet, the above query will return the full column of names of any model of Emp, but when the (lifted) query is run on Emp itself, Harriet will always be missing, i.e. we have:

| Query result on Emp: |

|

Query result on any model of Emp: |

|

Thus when unions are added to the query language, Codd tables are not even a weak representation system of missing information, meaning that queries over them don’t even report all sure information. It’s important to note here that semantics of UNION on Nulls, which are discussed in a later section, did not even come into play in this query. The «forgetful» nature of the two sub-queries was all that it took to guarantee that some sure information went unreported when the above query was run on the Codd table Emp.

For natural joins, the example needed to show that sure information may be unreported by some query is slightly more complicated. Consider the table

J

| F1 | F2 | F3 |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | NULL |

13 |

| 21 | NULL |

23 |

| 31 | 32 | 33 |

and the query

SELECT F1, F3 FROM (SELECT F1, F2 FROM J) AS F12 NATURAL JOIN (SELECT F2, F3 FROM J) AS F23;

| Query result on J: |

|

Query result on any model of J: |

|

The intuition for what happens above is that the Codd tables representing the projections in the subqueries lose track of the fact that the Nulls in the columns F12.F2 and F23.F2 are actually copies of the originals in the table J. This observation suggests that a relatively simple improvement of Codd tables (which works correctly for this example) would be to use Skolem constants (meaning Skolem functions which are also constant functions), say ω12 and ω22 instead of a single NULL symbol. Such an approach, called v-tables or Naive tables, is computationally less expensive that the c-tables discussed above. However, it is still not a complete solution for incomplete information in the sense that v-tables are only a weak representation for queries not using any negations in selection (and not using any set difference either). The first example considered in this section is using a negative selection clause, WHERE Age <> 22, so it is also an example where v-tables queries would not report sure information.

Check constraints and foreign keys[edit]

The primary place in which SQL three-valued logic intersects with SQL Data Definition Language (DDL) is in the form of check constraints. A check constraint placed on a column operates under a slightly different set of rules than those for the DML WHERE clause. While a DML WHERE clause must evaluate to True for a row, a check constraint must not evaluate to False. (From a logic perspective, the designated values are True and Unknown.) This means that a check constraint will succeed if the result of the check is either True or Unknown. The following example table with a check constraint will prohibit any integer values from being inserted into column i, but will allow Null to be inserted since the result of the check will always evaluate to Unknown for Nulls.[18]

CREATE TABLE t ( i INTEGER, CONSTRAINT ck_i CHECK ( i < 0 AND i = 0 AND i > 0 ) );

Because of the change in designated values relative to the WHERE clause, from a logic perspective the law of excluded middle is a tautology for CHECK constraints, meaning CHECK (p OR NOT p) always succeeds. Furthermore, assuming Nulls are to be interpreted as existing but unknown values, some pathological CHECKs like the one above allow insertion of Nulls that could never be replaced by any non-null value.

In order to constrain a column to reject Nulls, the NOT NULL constraint can be applied, as shown in the example below. The NOT NULL constraint is semantically equivalent to a check constraint with an IS NOT NULL predicate.

CREATE TABLE t ( i INTEGER NOT NULL );

By default check constraints against foreign keys succeed if any of the fields in such keys are Null. For example, the table

CREATE TABLE Books ( title VARCHAR(100), author_last VARCHAR(20), author_first VARCHAR(20), FOREIGN KEY (author_last, author_first) REFERENCES Authors(last_name, first_name));